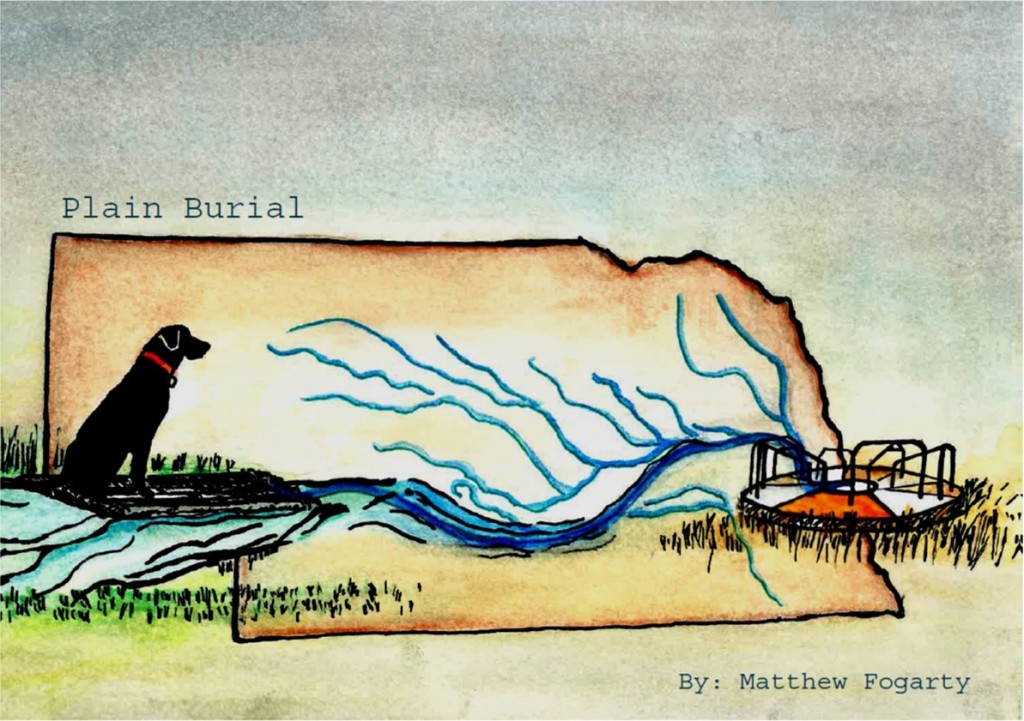

Matthew Fogarty

Bentley died somewhere in the middle of Nebraska. He was in the backseat and I didn’t see him right away. I’d been giving him tranquilizers to help keep him calm on the trip out west and when he laid down, I figured it was just the tranqs working too well. He wobbled a bit, looked woozy, and he did that low growl he does — more of a soft moan — when he wants something and doesn’t know how to ask and I told him to shut up and I turned up the radio.

We’d been on the road since early in the morning when I snuck him out of the Holiday Inn. They had a no pets policy and we skipped the free breakfast because of it. There wasn’t any way we would’ve gotten out without them seeing him and so I took us both out the back door near where all the semis park. He stopped and got up on his haunches to shit and I said, “We gotta go, B,” and yanked him out of it. I pulled over to the shoulder a few miles up and clipped on the leash and he ran around the ditch by the side of the highway for a couple minutes before finding his spot. He was always so regal, even in doing that; sometimes I’d offer him a newspaper. Still, I felt bad for the indignity of it, of having to do that basic living act with people speeding by. This time, he looked full of life, that big smile he’d get, like he was ready to run the rest of the the way to San Francisco. And then some asshole in a Land Rover slowed and blew his horn and whooped at us. My awesome dog didn’t hesitate: he barked and turned and shook his ass at the guy.

It wasn’t until the truck stop outside of North Platte that I realized he’d stopped breathing. It was a Love’s and there was a McDonalds inside and I lowered the windows a little and went in to get something to eat. I thought I’d seen his tail wag as I got out of the car. But he’d been quiet for much of the last hundred miles and the longer I was in line, the more worried I got. I ordered him a breakfast sandwich and ran back to the parking lot. He was in the same position as when I left, his body stretched on its belly on the back seat, his head resting between his front paws, his eyes closed. I said his name a dozen times and leaned my head next to his, put my hand near his mouth and his nose. There was nothing.

It’s not something I’d planned for. Yeah, he was getting old and he and I had been through a lot. I’d had him since he was two or three — those Lab eyes in the corner of the shelter were all I’d needed to see. Looking back on it, before we left Detroit, of course I had a feeling something bad might happen. It’s like most days, you imagine yourself just existing where you are and, going someplace new, it’s hard to see things working out perfectly, see all your life transplanted in one piece to a new place with new people. Everything feels uncertain. I was sure something would break. I just didn’t think it’d be Bentley.

# #

The thing about having a dead dog in the car is that he starts to smell pretty much right away. All the gases and bodily fluids no longer serve a purpose and start to jailbreak. I grabbed an old sheet from a box in the trunk and tucked it under him, still hoping that at some moment, his eyes would open and he’d get that long-mouthed smile and flip out his tongue at me, spray off a mohawk of slobber. It was his way of laughing. But he didn’t move, his body weighed down I suppose by the lack of life.

Once I got the sheet all the way under him, I sat back down in the driver’s seat and I lit up my phone and started googling where we were and how far we were from San Francisco and what the hell to do. In those first minutes, there was just that drained feeling in the stomach or maybe it’s a draining feeling. Something about to escape either way. And I looked up into the rearview and saw him shrouded on the backseat and that’s when I erupted. It’s just that we’d spent so many nights just me and him. He’d make faces and fold his body in all kinds of ways, bury his head in my armpit or my lap or lay across my feet or, when I got up for whatever reason, follow me, and then beat me back to the sofa, leap into my seat before I got there, and he’d do his mohawk laugh. I’d ventroliquize, give him words. Make him sound like a better version of me, happier.

Ashley’d just woken up when I called. “It’s beautiful out,” she said. “The fog burned off early. We should be eating pancakes.”

“Yeah that sounds great,” I said. I imagined her in a pink tee shirt and underwear, hair in a ponytail, in the bed we bought together last time I visited. “Hey something happened.” She asked what it was and I told her about Bentley. Tried to, anyway. I said, “I got — there’s this breakfast sandwich. It’s on the seat next to me. Bentley’s–“

“What is it?”

“He’s–” My mind filtered through all the kinder ways to describe it: passed, gone, lost, kicked the bucket, no longer with us, and so on. But all that came out was, “Fuck. He’s dead.”

“Oh babe that sucks. I’m sorry,” she said. There was something in me that thought it didn’t sound right, the way she said it. And it occurred to me then that she’d only met him the one time — last Christmas when she flew to Detroit and I showed her around the suburbs I grew up in and we went over to my parents’ house for dinner. My dad loved her and my mom did too once she was able to look past the fact there was some woman other than her in my life now. She’d always warned me against committing to someone too quickly, before seeing what kind of friend they’d make, but I told her Ashley and I’d had some great times together, that we were in love, and she seemed to agree that was enough. Bentley was unsure even after Ashley gave him a treat and took him for a walk. Those nights, he’d climb onto the bed and lay down between us, force us to move to the edges. I proposed anyway, and we spent that New Year’s outside along the riverwalk in the cold watching the fireworks reflect on the ice. It wasn’t ever a question for me, but still we had a long talk on Skype about whether or not I should bring him.

“Is there a doggy morgue or something there you can take him to?”

I can’t leave him here, I thought. “I don’t know. It’s Sunday in Nebraska. I think everything’s probably closed.”

“I can search the Internet for you if you need.”

“It’s okay. I’ve got my phone.”

“I don’t even know where you’d take a dead dog. Maybe, like, a pet cemetery? Do those really exist?”

“Probably. I don’t know. We only have twenty hours from here. I can’t think right now.”

“We used to flush our goldfish down the toilet.”

“I can’t leave him here.”

“Is there a hardware store that’s open?”

“Probably. Why?”

“Just — you could get a shovel and find a spot in a forest or something and bury him.”

“Bury him? I’m– I’m in Nebraska.”

“Just find someplace out of the way. They’ve got lots of land. We can get a new dog when you get here. If you want.”

“Are you being serious? I can’t leave him here.”

“You’re not going to drive twenty hours with a dead dog.”

I said I didn’t know and told her I’d call her later. “I love you,” she said.

“Yeah.” And that was it. I ended the call.

I looked again to the backseat, just to see if Bentley had moved, if maybe he was joking or begging for attention. He would do that sometimes and the longer we were together the more I found myself mimicking him with Ashley. Like the morning after she and I first slept together and I pretended to have a heart attack and pass out and she smiled and laughed and slapped my stomach. More than anything, I remember the light in her bedroom that morning, the sun filtering through her sheer curtains and the way it made everything seem so alive, her dark hair lit up blonde. The way she squinted with the light and without her glasses.

We’d met in line at a taco shop in Austin just as she was graduating law school and moving west and I was leaving grad school and moving home. There was that first intense spring month when we saw each other every night and there wasn’t any pressure because we were both leaving and we let ourselves explore, risk things, because of it. There was the way her naked body reacted when I curled up behind it, pressed back into mine feet first and then legs and then back like we were being zipped together, like the closing of a warm jacket. There were Skype calls and a bunch of trips to California after that, some more fun than others, some good days and great nights and a whole bunch of mornings too but there was something so sunlit natural about that first one that made us try to reproduce it if we could.

I’d left Bentley with my parents that year I was in Texas and I felt alone in the world because of it. Most times I didn’t have any doubt about Ashley; there were so many things that just felt right or at least more right than they’d felt with the other women I’d dated since college. And when one of her friends at the Academy of Sciences was hiring for an assistant curator, I was convinced there was some kind of fate thing going on that was pushing us together. But then, if I’m being honest, there were a few times that I questioned things, when I wondered whether she and I would have fallen in love so quickly if Bentley had been there with me.

# #

North Platte didn’t look like much more than a typical Oregon Trail stagecoach stop. Other than a couple of main streets in the center, it was mostly the big box stores and Walmarts and generic whatever stores that keep people trapped in these kinds of boring small towns. Even if he’d been alive, Bentley probably would’ve slept through it. And for that reason alone, it didn’t seem right to leave him. Even if I’d wanted to, according to the Humane Society’s website, the necessary city services were mostly nonexistent on the weekends. Breaking into a pet cemetery afterhours felt like the start of a bad horror novel. And the shallow roadside grave option was also wrong. Unlike most dogs, he wasn’t a big fan of the road. Without drugs, he’d get nauseous after a few miles, pace the backseat, and hang his face out the window, sick. It just wouldn’t be peaceful.

I thought about the river, the Platte. He loved the water, loved chasing thrown rocks to the lakebottom, and I thought maybe I could build a little raft and send him off to wherever rivers go. There was that brief moment of fantasy — Bentley cast off into the sunset like a dead Huck Finn — until I realized the river probably runs through someone’s backyard at some point and that there’d probably be some kid that’d have to go on living his life having once found Bentley’s decomposed body tied to a crude raft of sticks.

More than anything, I wanted him to come with me, both so I could be with him and he could be with me. He’d saved my life so many times.

So I drove.

I didn’t know where else to go and still didn’t know what to do. At the edge of town, there was a hardware store called “Ben’s Hardware” and it looked open, so I pulled off into the dirt parking lot thinking maybe I’d come up with something. It was an old wood building detached and away from the rows of sad storefronts of the downtown and there were bells strung to the door and inside, it smelled thick and sweet like old wood and the floors creaked. The old man behind the counter said hello and I didn’t really feel like talking, just nodded and kept going like I already knew where to find what I wanted. I assumed he was Ben, though his workshirt nametag said “Bill.”

The aisles were small and overcrowded with things and there were poles and fishing tackle hanging from the ceiling. In the back of the store, there was a section of camping supplies — compasses and knives and air mattresses and camp stoves and coolers, those kinds of things. “Need some help?” asked Ben or Bill, who apparently had followed me.

And that’s when the plan came together in my head: get a cooler, fill it with ice, and lift sheet-wrapped Bentley into it. “I need a big cooler,” I said.

“How big?”

“Big enough for a black Lab.”

BillBen smiled, deepening the ruts at the corners of his eyes. “Ha!” He looked at me, maybe waiting for me to say something. It was a thing Bentley used to do when I’d get home from somewhere. And with that thought I had to clench my lips and my eyes and I looked back toward the shelves. “Oh shit,” said BillBen. “I’m sorry, friend.”

“It’s okay.”

“I didn’t realize. My boy Roscoe, he died a year ago.” He had a hard time saying this. His hands looked weathered. “You’re not from here.”

“No. Traveling,” I said. “I can’t leave him.”

“I know it. You can’t. I’m sorry,” he said. “Biggest we got is fifty quarts. You probably need something bigger. Probably need a marine cooler. What’s his name?”

“Bentley.”

“Sounds like a big boy.”

“Yeah.”

“You probably need the seventy-five. Young’s Marine down by the river. Except he’s not open today.”

“There’s nowhere else in town?”

“Don’t think so. There’re the big places but not for this.”

“No.”

“I mean, the fifty might work. I just — if you buy it and it doesn’t work, I’m not going to be able to refund that money.”

“I know,” I said. I bought the cooler and took it out to the parking lot and set it on the ground near the back of the car.

“Need some help?” BillBen asked, again having followed.

“That’d be great.”

“Not something you plan for.”

“It’s really not,” I said. I opened the car and the force of the smell pushed me backward. It was offputting. There was the familiar sweaty smell of Bentley somewhere in it, but it was overtaken by the rest — mothball death and must and bitter and shit.

“How long’s he been gone?” asked BillBen

“Just a couple hours. We’re headed to San Francisco.”

“Wow. That’s a thing.”

“My girlfriend suggested I” — I started to say dump — “bury him by the side of the road.”

“No. You can’t do that.” He stepped in front of me, moved the cooler to the ground below the backseat, opened it, and lifted the two ends of the sheet to test Bentley’s weight. “Beautiful boy,” he said. I said yeah and he pointed me toward the other side of the car. “Get in there and hold his head. I’ll pull him out. Might fit after all.”

We moved him gently like a wounded soldier, lifting the four corners of the sheet slowly and keeping him from hitting the roof of the car. When he was halfway out and BillBen had started positioning the bottom of him in the cooler, I walked back around to help.

With his legs and tail folded under and his back arched and his nose straight ahead, he just barely fit in the open cooler. I had to press the top of his head down, point his nose at the ground, to be able to close the lid. He looked ashamed, like he’d gotten into something he shouldn’t have, his apologetic face, and I imagined him saying sorry: sorry for having ruined the drive, sorry for stinking up the car, sorry for every time I made you feel like I wasn’t listening, sorry for not being there in Austin. I guessed then that sorry was better than I told you so.

“Convenience store up the way,” BillBen said after we got the cooler up onto the backseat. “Get some ice, right? Cover him over. You can get back on the highway from there, make it straight through to wherever.”

“Thanks,” I said and shook his hand. I didn’t know what else to say. I was still thinking about what to do with my buddy, where to let him rest for good. BillBen stood there too in the sun, both of us probably thinking the same thought — something about what it means to be a friend and how rare a thing it is to find a good one.

“Well good luck to you.”

“Thanks,” I said. “Hey, I’m Sam.”

“Roger,” he said. He saw me look at the nametag and smiled, “Yeah, wife got it at a Goodwill. Nice and soft and worn in.”

“I love old shirts too,” I said. “I really appreciate the help.”

“Anytime,” he said and walked back to the store.

# #

What you have to understand about Bentley is that he was a dreamer. Most nights he’d take up half the bed, sprawled out on his side, paws toward my chest, and I’d wake up in the middle of the night to the paws twitching and his closed eyes twitching and his mouth twitching. His legs would flex and I could see him running in his dream and leaping. I always wondered what he dreamed about, where he was. And maybe it’s selfish or vain to think or maybe it’s just the personality I’ve made up for him, but I liked to think that maybe every once in awhile he dreamed about saving me from something. I had saved him plenty of times from cars or other dogs or chocolate, and I figured it was what we did. Part of our deal. We looked out for each other in our own ways. Sometimes I’d come home and he would be up on the windowsill watching for me, watching to make sure I got in safely. Or maybe he dreamed about Saturdays, chasing frisbees, the racetrack path he’d wear around the living room for no reason, just because, clearing the couch in two bounds, his paws barely touching it.

It had taken fifteen hours to get to North Platte what with us stopping every hundred miles or so for food or a walk, and I made it back to my parents’ house an hour quicker. I called Ashley when we were halfway home, told her I’d be a few days later than we planned. She said she wasn’t upset, just that she didn’t get it and I told her I didn’t expect she would and that I needed some time to think about things. As much as I wanted to picture her crying, pulling off the ring I’d given her, making sad margaritas with her friends, I could only imagine her going through her day like nothing, maybe even a little happy returning the special vacuum she’d bought to clean up the dog hair.

The light at the bottom of the exit ramp was red and there was something that hit me then: that it was where, if we’d been on a long trip, Bentley would first realize we were almost home and he’d stand up and press his face against my ear, like he was driving too, and he’d do it all the way to my parents’ house.

Their cars weren’t in the driveway so I parked and got out and entered the code to raise the garage door. It was getting colder out with the sun going down earlier and the red-oranging trees that always makes me feel like afternoons I’d come home from school and there wouldn’t be anyone in the house and it’d just be my parents’ dog and me or then later Bentley and me. I took my dad’s shovel, the one he uses on the driveway after a snow, and put it in the trunk on top of all my things and drove back through the subdivision.

I took us to the park — his favorite park — with the merry-go-round I’d convinced him once to jump and spin on. He thought it was hilarious and he did his round laugh and he tried to tackle me but he was too dizzy to see and ended up in the dirt under a bush. And I grabbed the shovel and rolled the cooler out onto the grass to the middle of the park and that’s where Bentley and I said goodbye.

# #

Born and raised in the square-mile suburbs of Detroit, Matthew Fogarty currently lives and writes in Columbia, where he is fiction editor of Yemassee. He also edits Cartagena, a literary journal. His fiction has appeared or is forthcoming in such journals as Passages North, PANK, 14 Hills, Smokelong Quarterly, and Midwestern Gothic.