This afternoon I scatter fresh strawberries all over her bare body—her breasts, her belly, her thighs, her you-know-what—and top them with Reddi-Wip. Then I proceed to eat them off, one by one, licking the cold Reddi-Wip around with my tongue. In between eating I take gulps of champagne. We usually have a bottle of champagne on the nightstand, and two of those fancy tall glasses. Flutes, she calls them. I always thought a flute was a band instrument, but she calls them flutes. It isn’t expensive champagne, it’s only Andre’s. But it’s what she likes to drink in the afternoon. Me, I’d rather have bourbon.

We’re making love in the master bedroom of her house, hers and her husband’s. He’s downtown at his office, of course. He always is, weekdays, nine to six or so, sometimes longer if he has a meeting or takes out a client. That’s his schedule except for two weeks a year, when they go to Cancún. And a few days around Christmas.

I say, “We can’t keep meeting this way,” which is very funny. Like how many days am I going to be eating strawberries and cream off her bod? “I mean, I’m going to lose my job if I keep spending so much time here. You don’t need a job, but I do.”

She tosses her head and looks around the bedroom. It’s big, especially if you count the adjoining bathroom. It’s one of those new McMansions the builders are putting up all over Houston these days, a brick Southern-looking house, with a huge family room adjoining an open kitchen downstairs, a tiny living room, a den, a computer room next to the den, and a large bathroom adjoining the master bedroom upstairs. That bathroom looks like a honeymoon suite at Las Vegas I’ll bet, complete with sunken tub, steam shower stall, bidet.

“You’re right,” she says. “He’s a jerk, but at least he’s a good provider.” She looks like a little girl when she gets intense. Or I should say, a little girl inside a big girl. She is big. She’s put on a lot of weight since she got married. But she’s still a looker. You can’t take away that drop-dead face. We’re both in our thirties now. Me, I stay in shape—go to the gym, play some basketball, that sort of thing. But she’s running to fat. Otherwise she looks good. Goes to the hair salon every week, keeps her hair blonde. Has a lot of clothes, buys a lot of jewelry. She could go out to lunch every day if she wanted, or meet friends at the country club. But she likes to stay home and drink. When does she start? Noon at the latest. And eat. She really likes to eat. Which is how I came to meet her again, after all these years.

The phone on the telephone stand starts to ring. “Let it ring,” she says, as I’m eating the last strawberry out of her you-know-what and she’s starting to shiver all over.

“It might be your husband.”

“So, I’ll tell him I was out by the pool.”

“Don’t you ever take your calls?”

“Didn’t anybody ever tell you not to talk with your mouth full?”

We met again when I delivered a ham to her door. It’s not River Oaks, but a neighborhood that’s almost River Oaks. More hoity-toity than West U., if you know what I mean. Lots of gravel and monkey grass. A Mexican always mowing the lawn and trimming the hedges. I’m a delivery man for Bogart Farms Honey-Cured Ham. The worst thing about working for Bogart Farms is the delivery truck. It has a round tin snout attached to the front, before the grille. It has pointed ears sticking up above the cab. It has a curled tin tail in back. And the whole truck is painted this very bright pink. I mean, really pink. Lettered on the back are the words,

FOLLOW ME TO THE HOME OF THE WORLD’S LARGEST HAM!

Whenever I’m making a delivery, kids point at the truck and make loud oink oink noises. It’s hard to feel good about yourself with kids pointing and oinking. And a guy who’s always being chased by bill collectors needs to feel good once in a while.

Every time the phone rings I want to hide. It’s always them. Sometimes not even them in person but a machine: “We have a very important message for you. All our representatives are busy, please hold…” Jesus—if it’s so fucking important, why can’t they put a human being on the line? Despite the fact my wife is a teller in a bank, she doesn’t understand money. We’re over-over-extended on all our credit cards, with no savings. My boss, Mr. Bogart, calls the truck the Pig Mobile and thinks it’s great advertising. Better than radio commercials, he says. The Pig Mobile was his idea. Well, it’s the best job I’ve had. It pays real benefits and all. Mr. Bogart has promised to promote me to Meat Clerk within six months if I work out, maybe Meat Manager after that, if I prove to be “Bogart Farms material,” whatever that is. Pure pork, if you ask me. Anyhow, I swallow my pride and drive the damned thing. Oink, oink.

The way I met Vera again was like something in a movie. The Postman Always Rings Twice with Jack Nicholson—you ever seen that one? I delivered a ham to the front door—a big one, fat trimmed, dressed fancy with pineapple rings, maraschino cherries, and cloves, and she takes one look at me and the Pig Mobile at the curb, and she says, “Wayne Smith! Or is it Porky Pig now?”

“It’s Wayne,” I said, not liking the pig reference one bit.

But Mr. Bogart says the customer is always right, so I let it go. Then I realized who she was. We hadn’t seen each other since senior year of high school.

“Vera Jenkins,” I said.

“Vera Serchuck, now,” she said, and flashed her big diamond ring.

“You haven’t changed a bit,” I said.

“Liar. Nobody’s home—why don’t you come on in? We can talk old times.” She was wearing a chartreuse halter and black shorts. Her legs were still damned good.

“Maybe for a minute or two. I’ve got lots of deliveries to make.”

The next thing I knew, we were sitting in her family room with the TV on and drinking glasses of champagne. Mr. Bogart would kill me. We’re not supposed to drink on the job, not even a beer with lunch.

“Isn’t this refreshing?” she said. “I always say, champagne is very refreshing.”

“It is that,” I said, though I’m a bourbon man. Jack Daniels if you’re paying.

“So what have you been doing since high school?” I asked.

“Pretty much what you see is what I got,” she said with a wicked laugh, gesturing around the paneled room. The paneling didn’t look like that fake stuff that goes up in sheets. It looked like the real thing, individual slabs of walnut. “I went to A&M for two years, met Al, and got married. He was two years ahead of me and couldn’t wait for me to graduate. He already had a real estate job here in town. We had us a honeymoon in Hawaii, then he started work, and we started working on child number one. How about you?”

“Got a football scholarship to UT, but had to drop out. Ruptured my spleen in a freshman scrimmage. Just a series of jobs since then. Nothing special. You know how it is without a degree. No big deal.”

“I don’t see a wedding ring.”

“Never wore one. Not my style.”

“But you are married?”

“I am that,” I said. “It’s not so good any more. You know how it gets.” I thought of my wife’s heavy, veined legs, with cellulite on her inner thighs.

Before I knew it, Vera was in my lap, saying in my ear, “Want to pork me, Porky?”

That first afternoon we took the champagne bottle up to the bedroom and she pulled off her halter. When I stepped out of my boxer shorts she said, “Wow! Home of the Whopper!” I know I’m bigger than average. I’ve known that since gym class in junior high.

“Pork me, Porky,” she kept saying. I hated that goddamn pink truck.

The next week when I was looking over my delivery list, I saw her name and address again. “That Vera’s eating a lot of ham,” I said to myself.

“You can put it in the refrigerator,” she said when I appeared on her doorstep, carrying a ham like a football.

“Isn’t your husband going to ask why you’re ordering so much ham?”

“I order it because I like it,” she said, and grabbed my you-know-what. That afternoon we assumed the missionary position and I liked it a whole lot better.

“Pork me, Porky,” she said.

“Wayne,” I said, thrusting. “My name is Wayne Smith.”

There was a TV in the bedroom too, and she liked to keep it on. Usually I arrived during Days of Our Lives, stayed through General Hospital, and left when The Jeffersons rerun came on. Sometimes she switched channels to The Muppet Babies, but not often. The central air conditioning was cool on our bare skin. She had satin sheets. I guess you’d call them lilac.

Of course that damned truck was a problem. I always worried the neighbors would start to talk, maybe tell her husband a Pig Mobile was parked in front of his house for hours at a time. (“An Oldsmobile?” I could hear him ask. “No, a Pig Mobile!” they’d reply.) I started parking the thing around the corner and walking to her house. She has a white Lexus with tan leather seats and a moon roof, but it stays in the garage most of the time. Her drinking, I wonder? She says her husband drives a black Mercedes. I’m sure he does.

“Hey, you don’t have to keep ordering these hams,” I said one day. “I’ll come see you anyhow.”

“I order ham because I like ham,” she said. “And because my husband happens to be Jewish and I like to spite him.”

“You eat them all yourself?”

“Me and the boys. They like ham and cheese sandwiches for lunch.”

I kept worrying her husband would come home unexpectedly, but he never did. (Reminds me of the old joke, What are the three words you never want to hear when you’re making love? “Honey, I’m home!”) I worried one of her two boys would come home from school after skipping practice, but they never did. She asked if we had kids. I told her we’d lost a little girl and never had another. Tiffany was her name. The wife and I agreed that when your last name is Smith, it’s important to give your child a distinctive first name. Tiffany was hit by a car, when she ran out in the street after her cat.

The cat’s name was Miss Kitty. Sometimes I dream about that little girl. I had her name tattooed in purple on my right bicep. Purple was her favorite color. Vera had never mentioned the tattoo before—maybe she thought it was the name of a former girlfriend. Or maybe she thought it looked common. I’m sure none of her husband’s fancy friends had tattoos. But after I told her about Tiffany, she bent down and kissed my arm.

I started getting behind in my deliveries. (I was going to say, I started getting a little behind in my deliveries, but I’m not a good joke teller.) Vera would want me to stay longer and longer, open a second bottle of champagne. That stuff could give you a headache, after a while. And I couldn’t check in at Bogart’s smelling of alcohol. It got to be a problem. People were calling Bogart, asking where in hell was their ham? Company was coming for supper at five, and they had no ham. Mr. Bogart told me my performance was slipping. I told him I’d do better. He told me I better do better, or he’d put me on notice. There were lots of good drivers out there.

Then this afternoon she’s really getting in to it so I stay on, right through Oprah and half-way through Jeopardy.

That’s when she gets up and gets the strawberries and Reddi-Wip from the kitchen, and we start fooling around. Sure it was fun, but I was worried. She’s so into it, I’m afraid we’ll run into the five o’clock news. Then we’re both in trouble. (“Honey, I’m home!”)

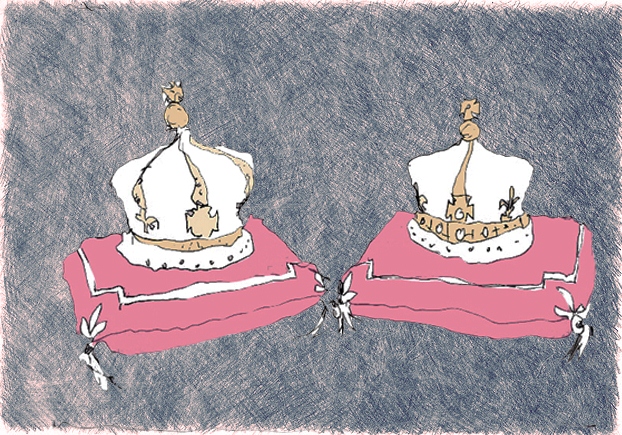

Suddenly she said, “Remember our senior year? When we were elected?”

“Sure do,” I say, wiping Reddi-Wip off the tip of my nose.

“I never thought I’d be elected May Queen.”

“I did. Everybody thought you’d be May Queen. You were the prettiest girl in the whole class.”

“I never thought so. My nose is too broad. I thought Betty Culver was prettier.”

“No way. Betty Culver was a stuck-up bitch.”

“But pretty.”

“You were prettier. Still are,” I say, seeing this overweight peroxide blonde under me, wearing nothing but all jewelry and gold chains. I know it was peroxide, because I saw her dark roots. Of course I also saw her dark you-know-what. She still had that fantastic face, though it was always too white. I guess she overdoes the face powder. She has love handles all around. “It was my being elected that was the surprise.”

“Why? You were starting quarterback!”

“But you were going steady with Sammy. Sammy Spain. You wore his class ring. Everyone just assumed because you were a couple, you’d both be elected. May King and May Queen.”

“Well, it didn’t work out that way. Lots of girls were sweet on you. Especially after you hurled that Hail Mary pass to Junior Kelliher and we won the big game against Lamar. That pass must have been fifty-five yards! You were a real hero.”

“For a day.” I recall the burst of cheers from the bleachers. Then I think about all the undelivered hams out in the Pig Mobile.

“No, much longer. That’s why they elected you May King. You were a hero. I hardly knew you, it was such a big school. You ran around with a different crowd. But I knew who you were, all right. I was proud to have you as my May King.”

“I was proud.”

“We both were proud. Wasn’t it a beautiful day?”

“As I recall, it was a perfect day. Lots of sunshine but not too hot. Low humidity, for Houston.”

“Wisteria and magnolias in bloom! I could smell them in the air.”

“And everybody came.”

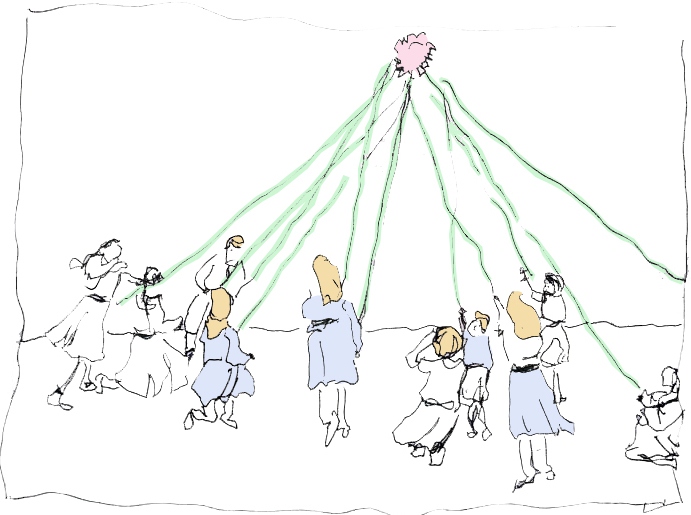

“Everybody! It was a turnout just like for homecoming. Remember the maypole dance?”

The phone rings. I jump. (“We have an important message for you…”). But she ignores it

“And my court—the Queen of the May’s Court. All wearing pastel prom gowns and dancing barefoot around that pole. That pole festooned with pastel ribbons . . . and they hung on, they hung on. Hey — I have some hair ribbons somewhere. Let’s festoon your dick with ribbons. It can be the goddamn maypole.”

I talk her out of that. What man in his right mind wants a festooned dick?

“And the band played Country Gardens, while my court danced around and around…The Maid of Honor was Becky Tull. No beauty, but she’s full of personality.”

“You wore white? I seem to remember white.”

“Of course I wore white! A white gown trimmed with white eyelet. God, I never felt prettier in my whole life. I felt prettier than I did in my wedding gown from Neiman Marcus.”

A pause. “Sure were pretty.”

“And you were so handsome! I remember you wore a white cutaway, complete with tails.”

“Only time I wore tails. Got married in a business suit, and a brown one at that. Best man took the white tux back to the renter’s shop next morning.”

“We came out the front doors of the high school. Do you remember those big front doors? Up above them, chiseled in the stone, were the words, HE WHO DOES NOT ADVANCE FALLS BEHIND.”

“That was the school motto.”

“God, I thought it was deep. But I’ve since wondered—if you don’t advance, couldn’t you sort of stay in place?”

I sip champagne. By now it is room temperature and sticky. “I couldn’t say.”

“The band struck up a fanfare, and we came out those big front doors and everyone applauded. We marched around the audience and everyone bowed as we passed by. Two little girls scattered rose petals in our path. We climbed some rickety wooden steps—I was afraid I’d catch my heels—and mounted our thrones. The music stopped and the crowd hushed and the principal, Baldy Dickerson, stepped forward and crowned us. They were just cardboard crowns covered with glue and dime store glitter, but honey, they were crowns!”

“And we had wands made out of tinfoil. We waved them at the crowd.”

“Cardboard and tinfoil, can you imagine? But it was all so grand.”

“Baldy Dickerson’s dead now.”

“Dead as a door nail.”

We sit silent for a moment. Then she says, “Where did they go, Wayne?”

“Where did who go?”

“The Queen and King of the May.”

“They’re right here,” I say. I flex my Tiffany bicep, but she doesn’t kiss it. She sits on the side of the bed, her plump body smeared with strawberry juice and Reddi-wip. She’s holding the champagne flute but it’s empty.

Robert Phillips is a prolific author and poet, as well as the former Director of the Creative Writing Program at the University of Houston. His honors include a 1996 Enron Teaching Excellence Award, a Pushcart Prize, an American Academy and Institute of Arts and Letters Award in Literature, a New York State Council on the Arts CAPS Grant in Poetry, MacDowell Colony and Yaddo Fellowships, a National Public Radio Syndicated Fiction Project Award, a Syracuse University Arents Pioneer Medal, and Texas Institute of Letters membership. In 1998 he was named a John and Rebecca Moore Scholar at the University of Houston.