John A. McDermott

And you, Leigh, I wonder how you are, but, of course, you never tell.

And you, Leigh, I wonder how you are, but, of course, you never tell.

I’m sure I’ve told you all this before. Maybe after a boozy evening, maybe in a tearful apology. Maybe you’ll remember.

My mother hated my father’s brother, but we visited him several times a year, at least, until I was fifteen (four years before I met you, eight years before we married). My father went to Uncle Dixon’s place more often. Sometimes I tagged along, but most times he’d vanish on a Saturday afternoon or a Wednesday night and when I’d ask my mother where he was, she’d tell me, “Nowhere,” or “With nobody.” I knew what she meant. To my mother, Uncle Dixon was Nobody living Nowhere. And she was mostly right.

I remember you once, euphemistically, remarked my mother was “firm in her convictions.” Firm, yes. Well.

I earned my driver’s license not long after the time my mother declared, “Enough. No more,” to our family visits to Dixon’s place and then I’d sneak off myself, driving my battered green Oldsmobile along the winding roads between Nacogdoches and my uncle’s place on the outskirts of Shreveport. It was a nice vista: rolling hills, tall trees, the thick pine forests of east Texas and Louisiana. But always, dotting the countryside like fire ant bites on a beauty queen’s legs, were pockets of open poverty. Shacks, abandoned cars, yards piled high with random clutter. Peeling paint and warped wood. And dogs. Always a few loose dogs, some which ended up dead in the middle of the highway. These were people who could barely feed themselves, yet they had dogs. My father called them, “Damn dogs,” and even as I went through the typical boyhood longing for a companion of Lassie’s or Rin Tin Tin’s character, I knew to stay silent. Uncle Dixon had Damn Dogs, a string of them over the years, often in pairs or trios; my father did not.

Uncle Dixon lived in a particularly oozing stretch of ramshackle homes and gone-to-seed yards spotted with tall grass. I remember my mother cursing the approach to his place. “Liquor store, tavern, liquor store, tavern, strip club, strip club, strip club,” she said, her voice low and sharp and disgusted. “Really, Joe, do we have to come all this way for this?”

“You exaggerate, Sue Ann,” my father said.

She would stare at him and ask, “Don’t we have better things to do?”

“I’m sorry, Sue Ann,” my father said, would always say, “but Dixon’s my brother.”

She’d cross her arms over her shirtdress. She had the same dress in multiple colors and it’s what I most clearly remember her wearing: red checks or blue checks or yellow checks. They were always one color, cotton, and short sleeved.

“What do you want me to do?” He looked straight ahead, though I couldn’t see his eyes behind his dark glasses, and gripped the big steering wheel like he was waiting for it to buck. Steering wheels were larger then—built as if to maneuver ocean liners, things that were difficult to turn around. “Ignore him?”

“That would be a start,” my mother said. “A good, good start.”

And next time my father would sneak off alone.

I understand sneaking off, Leigh. Really, I do. My father, my mother, myself. Everyone slinks off at some point, a wary glance over the shoulder, the right-left-right check of the soul, the clammy hands on the doorknob, on the wheel, on the money in the pocket.

* * *

Uncle Dixon was lean and tall with wavy gray hair—it had been dark once, nearly black like my father’s, and the curls were rimmed with white shadows that showed when he ran his thick fingers through the shaggy cut. It was getting thin on top, but he never tried to mask the inevitable—no comb-overs for Uncle Dixon—and never shaved it to embrace the clean look. His hair hung in his face, hung to his stooped shoulders. He’d brush it away with his tan, gnarled, once-sailor, once-carpenter hands. I marveled at his bloodshot blue eyes; the gaunt, whisker-stubbled cheeks; the lines around his thin mouth and the deeper ones on his forehead. He smelled like cigarettes and gasoline and pine trees. My father told me it wasn’t pine I smelled, it was gin, but how could he tell? Uncle Dixon lived in a Loblolly forest. Uncle Dixon lived in a forest of bottles, too: green glass, clear glass, squat bodies and short necks, narrow fifths and longer necks.

When my father and mother brought me, we drank Cokes out of small glass bottles and sat on the porch of Uncle Dixon’s weathered wooden house. Two bedrooms, a small living room, a smaller kitchen. It had been white once, but turned a sickly gray. Too much heat, too many storms. Sometimes I’d play out back while the adults chatted—or rather, my father and his brother chatted, my mother steamed—and I’d flick at the paint with my fingernails and tear off inches-long strips of it, like scabs peeled from my knees. (Perhaps this is where I began that ugly habit, picking scabs. You’d slap my hand, more like a mother than a wife.)

There was more stuff piled behind the house: dead cars, dead air conditioners, a dead tractor, and a few dead bicycles. A couple times I found dead animals back there; a fly-covered raccoon in the backseat of a tire-less Chevrolet; a dead armadillo between a doorless refrigerator and a pair of cement blocks. I remember the television commercials on Saturday mornings warning of the dangers of getting trapped in abandoned fridges. I thought it was good citizenship of Uncle Dixon to remove the door. I told my mother.

“I doubt much if he was thinking of your safety,” she scoffed. “He probably traded it for a bottle of hooch.”

“Who needs a door without the rest of the refrigerator?”

“Don’t sass,” she’d said.

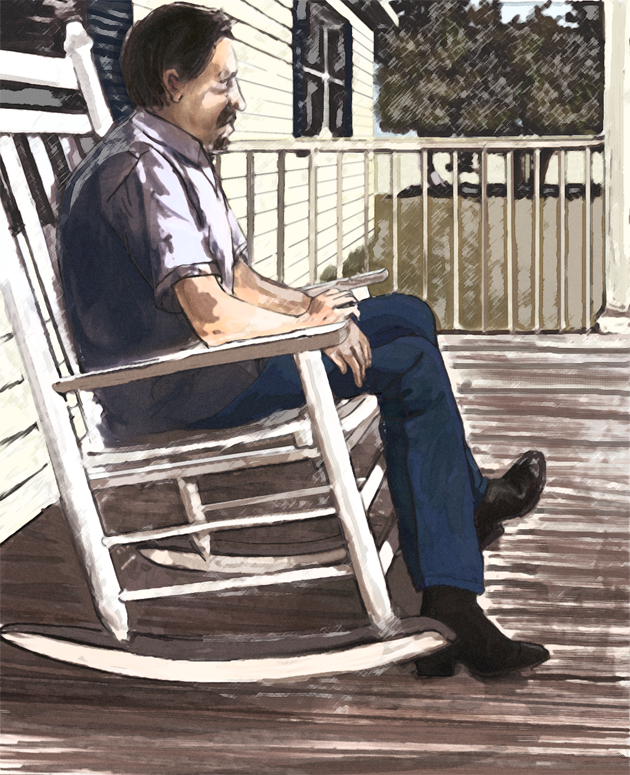

When my father started taking me without my mother, he didn’t drink Coke, but I still did. The men would sit in the same spots on the porch, as if my mother were still there, leaving the best seat open for her, and they’d sip whatever it was my Uncle had in stock. Mostly brown liquor, bourbon, I suppose, for my father, and watery-looking shots for Uncle Dixon, though I doubt very much it was only—or ever—water. The older I got, the closer I’d keep to the conversation, listening while I hovered at the side of the house, my hand resting on a scarred sill or I’d sit, my back against the peeling paint, and toss rocks into the woods growing thick on three sides of Uncle Dixon’s property. There was only one way in and one way out, along that blotted road my mother admired so much.

“She’s telling me to stay,” Uncle Dixon said one Saturday afternoon in late spring. “I won’t be leaving this place.”

“Dix, she’s not telling you a damn thing. She can’t.”

“She is, Joe. She is.”

“Well, if she’s telling you to stay here, she’s wrong. Or she wants to keep you down.”

Uncle Dixon stood, knocking over a frail spindle-back chair, and wavered in front of my still-seated father. “Desirae knows what’s best, you son of a bitch. You ever say different, we’ll have words.”

My father sipped from his glass and shook his head. “We have words about that woman all the time, Dixon. And you know I’m right. It’s time to move to town. Leave this hole.”

Uncle Dixon jerked like a pitcher picking off a runner at second and hurled his bottle into the woods beyond my side of the house. The glass hit a trunk and shattered, shards raining into the leaves. He swore, more grunts than curses, and my father was silent and then Uncle Dixon was silent, too. I listened to the woods. Somewhere a woodpecker beat his beak against something hard.

“You could kill something doing that,” my father said quietly.

“Not likely.” Uncle Dixon righted the chair and sat. He already had a new bottle in his hand and he screwed off the cap. He offered some to my father, who shook his head.

“I noticed you threw an empty,” my father said. “Wouldn’t chunk good liquor, would you? Even pissed as hell.”

“Waste not, want not.”

My father called me to the car and we drove back to Nacogdoches. We listened to the radio and my father chewed Wrigley’s, conscious of the smell of liquor on his breath. He never told my mother about our trips and she never asked. At least not in my earshot.

***

The woman who insisted my uncle stay in the woods was Desirae, his girlfriend, maybe his wife, I was never quite sure. I guess I met her, when I was very little, but if I remember anything it’s more a memory of a memory, or maybe a memory of something I was told, rather than anything crisp. A woman with dark hair, a loud laugh, friendly, a feeling I remember liking. Nothing like you, really, except the hair.

You were much quieter, much more solemn. But I made you laugh, didn’t I? We did. It’s hard to remember now, Leigh. I swear I remember Desirae better each day, and you, you fade by the minute. Not the sense of you, but your eyes, the lilt of your voice, the curve of your back turned to me in our bed, the warm steadiness of your breath in the night.

Let’s leave that, go back further again. There was a day with barbecued chicken and blueberry muffins in August and a bear at the edge of the woods. He’d come, called by the smell, and Uncle Dixon and this woman, she must have been Desirae, laughed and called to him and my mother ran into the house and locked the bathroom door and my father went to our car and pulled his gun from underneath the driver’s seat. He always carried one there. My father was a lawyer and worried about unhappy clients, unhappy ex-cons. The gun—one he’d had since the Second World War—was the only one in our house. My father didn’t hunt, though he’d grown up with it, and didn’t talk much about guns.

Uncle Dixon had them all over his house, but mostly they didn’t work. He salvaged them, tinkered, brought them back to life. It was never the same guns on his work table, so he must have sold them and acquired new ones. He laughed at my father, told him to put his pea-shooter back in the car. If the bear was fool enough to charge, Uncle Dixon had something bigger in mind. But he and Desirae—yeah, it must have been her—laughed and sipped their drinks not twenty feet from the bear, who grew tired of entertaining them and lumbered back into the brush. My mother came out of the bathroom and told my father he was reckless and we had to leave. He told her, his voice low, “No, Sue Ann, we’re staying.” And we did, that time.

The chicken was delicious. I remember the red-brown sauce on my fingers, the muffins on the side of my plate. Two. Desirae had given me a second. I don’t remember her after that, but I remember the moist meat, the sweet berries, the rush of fear and frustration pulsing from my mother, quiet behind a scowl, and my father’s lowered eyes.

Desirae and Uncle Dixon’s laughter grew screeching as the afternoon turned to dusk and we drove back in the dark, the thick trees crowding around us like spectators chasing us, circling us, itching to watch a fight.

***

My parents separated when I was a junior in high school, my mother moving back to San Antonio where her people still lived, my father staying in the house in Nacogdoches. He wouldn’t leave his practice and didn’t want to even if he could. I refused to leave my high school, the friends I’d known all my life. San Antonio was the other side of the moon to me then. (And yet we met so much further away, Manhattan, that summer in the city. You came to visit East Texas once, reluctantly, and hated the wildness, the isolation. Why do you linger now? Why don’t you haunt the streets of New York instead of me, here, back in Nacogdoches? Go away, I want to say, but never do. Not even now. Don’t go.) My father suggested, in light of losing the only woman in our lives, we make our home a stag’s refuge. He invited Uncle Dixon to stay with us in one of the early months. It didn’t work out. There was Uncle Dixon, with his own stash of ketchup and salt-and-pepper packets stolen from restaurants, his contribution to our efforts, standing in the walk-in pantry, eye-level to shelves of soup and bags of rice, bottles of soda stored on the floor, boxes of cereal and jars of mushrooms and pickles. He shook his head and asked if we had a fallout shelter to match.

“Goods enough for the apocalypse,” he muttered.

“My mother is always prepared,” I said. (You said the same about her, in our first year, when she sent us The Joy of Cooking, a travel first aid kit, and a flashlight the size of a small suitcase. We wondered what sort of disasters she anticipated. The power went out in the city that August, just for a night, and we used that flashlight to find candles, the stubs of candles, and when the candles threw ghosts on the ceilings, danced in the corners, you used the flashlight to shoo them away with a brighter beam. My mother was right. Not often, but then.)

“Then what’s she doing in San Antone?” Uncle Dixon read the side of a can of cream of potato soup and put it back in its place. He wiped one finger looking for dust but there was none. “Didn’t she see this coming? This divorce? That’s what a prepared woman would have seen.”

I scuffed one loafer against the checked linoleum floor. I was still in my school clothes. My father insisted on conservative dress. No dungarees for him. “I think she saw this coming. Heck, I think she made it come. She’s probably got a new pantry already stocked down there.” I left a black gummy streak on one white square. Uncle Dixon glanced at it.

“I can respect that,” he said. “Be prepared. Like the Boy Scouts say.”

“You were a Boy Scout?”

“Once. Once upon a time. I haven’t always been an old lush.”

We were silent for a moment.

“I didn’t say that,” I said.

“No, you didn’t.” He smiled. He walked to the counter and plucked a pencil from a half-dozen my mother kept nesting in a tin by her pad of paper. She was always making lists. “But I bet you’ve thought it once or twice.”

“Maybe once.”

“Or twice,” he said. He bent to the floor, turned the eraser side of the pencil to the streak, and rubbed it away with a few quick swipes. He brushed away the stray pink crumbs. The square was clean. He stood and picked up the soup can. “This looks tasty. Let’s have lunch.” He handed me the pencil and pointed to the counter. I tucked it in among the others, as if my mother would want it in its rightful spot, as if she might walk in and scold me if it wasn’t where she needed it.

I left things in their spot for you, too: a trio of perfume bottles on our dresser; an open box of sanitary napkins in the bathroom closet; a pink plastic comb, missing three of its teeth—the comb I watched you use after your bath, after swimming. Your damn plastic comb.

***

Around the time of my mother’s move, I learned Desirae was dead, had been dead for a good while, since shortly after the evening of the bear. Uncle Dixon always spoke of her in the present tense, but my father corrected me one evening when I asked where she was living.

“She’s not living anywhere,” he said, snubbing a cigarette out in a glass ashtray on the coffee table in the parlor. Since my mother’s departure, he’d taken to smoking in the house, at least the downstairs rooms. He didn’t smoke upstairs. He didn’t want to fall asleep and kill us both some midnight, he said. I thanked him for that, but he told me he could change his mind any minute—it was his house and if he wanted to smoke in bed he damn well could. I didn’t thank him again for anything for a while after that, but he didn’t smoke upstairs, ever, as far as I know.

“How’d she die?”

“She was shot by a man in a bar.”

My mother’s parlor was light blue. In the dusk it looked darker, but I knew the room was pale. Pale blue rugs with white trim. We sat on a pale blue couch with polished wooden legs. There was a large mirror over the mantle in a gold frame. I listened to the pale blue room. The tick of the grandfather clock. The anonymous creaks from the hallway, the kitchen, the upstairs. It was only the two of us home, but the stray groans and clucks populated the place with invisible, heavy-footed spirits (residents, like Desirae at Uncle Dixon’s, you, here, now).

My father took another drag.

“Why’d the man shoot her?”

“I don’t quite know. You should ask him.”

“How can I do that?”

“The man was your Uncle Dixon.”

I remember flinching as if something had flown by me in the dark, a bat winging by my head. I may have even waved it away. “Really?” I was holding my breath and I didn’t know why.

He lit up a new cigarette and shook his head. “No, I’m making it up, son. Just to shock you.” It took me a moment to hear the sarcasm in his tired voice.

My father never went to his bed that night. He slept, still in his tie but shoeless, on the pale blue couch.

Leigh, the night you left, I drank our vodka. I played the stereo. Billie Holiday and Miles Davis, your favorite albums. I drank some more, ate the rinds of the lime I’d been slicing and dropping into the icy glass. Opened a tumultuous bottle of tonic and soused the kitchen floor, the little stovetop, the handle of the refrigerator in our cramped galley kitchen.

I didn’t kill you. You left of your own accord. You took your keys, Leigh, and I never ordered you into or out of that car. You never phoned that night, to tell me where you’d gone. Maybe you should have taken that enormous flashlight, for as much good as it’s done me since. I’m not even sure where it is. A storage unit in New Jersey, I guess, where I finally took the rest of our belongings.

There wasn’t much of the bottle to finish, but it did the job.

***

Uncle Dixon disappeared the spring before I met you. His departure is the reason I left Texas, went off to school. Met you, married you. With just my father, there was no reason to stay. Without Uncle Dixon, we wouldn’t have had the decade we did.

It was Easter of my senior year. My mother, permanently returned to San Antonio, was already seeing the man, Charlie Maris, a dentist, she would marry by Christmas. My father was away, avoiding the holiday, securing an affidavit in Houston. He lured Uncle Dixon to stay with me that weekend. What did my father fear, leaving me alone? A houseful of my friends, a beer-soaked bash, Louie, Louie blaring from the speakers? We were graduating soon, young men eager to slip the yoke of childhood and explore. Some of us did. The jungles of Viet Nam. The distant shores of California. I went East. That, Leigh, you know too well. I imagine you waiting there for me, with your sly smile and long hair, longer legs and patience. Washington Square Park and blue jeans. Your naked feet and painted toenails, the soles of your feet black from Manhattan cement. I was astounded anyone would walk barefoot on the sidewalks, so willing to get dirty. You once told me I was scared to get sullied—your word, Leigh, sullied.

I asked Uncle Dixon about what my father had said. What did I have to lose? He was making ketchup soup, something a hobo would have found familiar, letting me drink bottled beer as we sat at the kitchen table. His hair was nearly white then, just splotches of shadow where the younger man had been.

“I didn’t kill Desirae,” he said. “I never killed her. They said I shot her, but she left that bar. She mighta took off. Went off with another man. Now she is dead. I admit that. Hell, I know that. She came back.” He laughed. He pointed the dripping spoon at me. “She’s with me all the time, long as I don’t stray too far.” He stirred and tasted, his thin lips pursed in a kiss. Stirred some more. “She’s here right now. You feel her?” He stared at me and smiled. “She’s always with me.”

My hands stuck to the wet bottle. I believed him. Desirae was somewhere in the kitchen. In the chair beside him, hovering above the stove, leaning against the pantry door. I couldn’t see her, but Uncle Dixon could. He stirred the bowl of ketchup and dribbled water from the tap, then added more ketchup, thinning, thickening, thinning, thickening, until he had it right. He’d run out of pepper packets, but that was okay. He had a sleeve of stale soda crackers. That salt was seasoning enough.

He hummed while he concocted and I remembered my mother’s curse, a nobody living nowhere, and the litany of sins leading to his and, I guess, Desirae’s place, liquor store, tavern, liquor store, tavern, strip club, strip club, strip club. Satisfied with the steaming saucepan, he poured three cups—one for me, one for himself, and one for a guest, who I didn’t need to guess.

That night, Uncle Dixon told me how he met Desirae, how he’d loved her and she’d loved him. He told me stories. He laughed. Her soup grew cold as ours diminished and there were moments, no, minutes, when I was certain if I’d reached across the cluttered table to touch her arm, she would have been there, a resistance, a roundness in the air. When he burned his mouth, he swore, once, and smacked his lips. “I shouldn’t a told that joke at your expense, dear,” he said, not to me, and dipped his head toward her space.

I never saw Uncle Dixon again. His last Damn Dogs were the reason we learned he was gone. Someone had called the sheriff on the loose hounds, sharp and skinny as swords, and my father was rung up as caretaker. Uncle Dixon’d abandoned it all; the gray house, the littered woods, the latest guns, the sea of empty glass.

My father lost himself, chainsmoking Pall Malls and composing briefs, the firm—his career—as antidote and cancer. You declared, without knowing him, that he was dying by design. (He did and I told you not to join me for his funeral. You stayed behind. I went alone and hurried back, anxious to touch you again. Truth be told, to fuck you, to get inside you and never come out. And we did. I remember the night I returned. It was as if you’d read my mind.) My mother never showed; no one asked about her. Her actual appearance would have been redundant. She was all over that church anyway. All over everything.

Uncle Dixon and I ate the rest of that Easter meal in silence, as I do now, tonight, at a table set for two, in a house dark as a blackout. It is summer in Texas, hundred-degree days, with humidity as thick and hot as a wool sweater. And yet I made soup, weak and watery and plain, bodiless as a ghost. The ceiling fan spins above me in the shadows, its soft breeze subtle as the flight of a slender, circling bird. What I thought were once doves, I suppose are now buzzards.

Leigh, I didn’t kill you. I didn’t mean to drive you away. After you left—for where? I lie and tell myself Delaware. Maine. Nova Scotia. They are prettier possibilities—what was left of you, they told me, wasn’t enough to bury. I couldn’t stay in the city. I had to come home.

My father is buried in the new cemetery on the outskirts of town, by the housing lots and the half-finished hospital. My mother thrives with Mr. Maris, playing golf with his children and grand-children in San Antonio. Uncle Dixon disappeared years ago. He just vanished, too, like you, like Desirae. Decayed out there somewhere, I bet, with the raccoons and the armadillo. Does his lover watch his spot in the forest, protecting it, protecting him? Or does she lurk and flit in that life, too?

I sit here smoking cigarettes and listening to music from a lifetime ago, spinning on heavy records. So why do you follow me here, Leigh? I want to say, Leave. Stay. I don’t know anymore. I’m reduced to communing and consuming like the men in my childhood. Dark and quiet rooms, thin meals, too much liquor. And you, god damn you, Leigh, you are always right here: in this house, not even our house, here, even as I sit in this kitchen, sloppy, gin-soaked and sullen, sipping bitter soup, salted with tears of my own making.

And then I tell myself, I didn’t do any of this. I’m sorry, but I didn’t do anything. I have nothing, Leigh, for which to apologize.

John McDermott is a native of Madison, Wisconsin and now teaches at Stephen F. Austin State University in Nacogdoches, Texas, where he coordinates the BFA program in creative writing. His stories have appeared in Alaska Quarterly Review, Cream City Review, Meridian, Southeast Review, and elsewhere.