Foreword

Rick Moody and I are sitting in Houston’s Rothko Chapel in the semi-darkness. We’re both trying not to bust out laughing. I watch Rick scan the paintings, walls, take in the entire moment, and see from the expression on his face he’s thinking how unique this place is and a few other thoughts best not mentioned here. He shoots me an amused look and we both haul absolute ass for the outside sunlight before we lose it.

I’ve been out on the road with Moody a few times—New York City, the Pacific Northwest, and when he rolls through the greater neighborhood for Texas hangs. From the late-night endless bizarre banter over shared meals and conversation, I’ve come to know him as a savant of words. In his piece for Story|Houston there is a stunning richness of language that can bend minds, throw you down cerebral tangents of your own, and ask that you, as a reader, take your time and bring your A game.

It’s no secret that life is fragile and people come undone over the strangest things. What we allow to pull our strings can say a great deal about us as quirky and necessarily human. Sometimes we make a stand for what we think, at that moment, matters. We need look no further than our own love lives to examine how these attitudes have either kept us on board or caused us to jump ship. But turkeys? Hell yes, why not? Wars have been fought over less.

Moody is a sensual, thoughtful, and brilliant man with an impeccable understanding of how writing can be used to expose both the surreal and the mundane. His work over the years is nothing short of mesmerizing, beautiful, and flat-out hilarious, and this piece is certainly resplendent, stellar, and, most importantly, classic Moody, writing at its most sublime and stout. Enjoy the ride.

Nathaniel Riverhorse Nakadate

The Turkeys of Marfa

Rick Moody

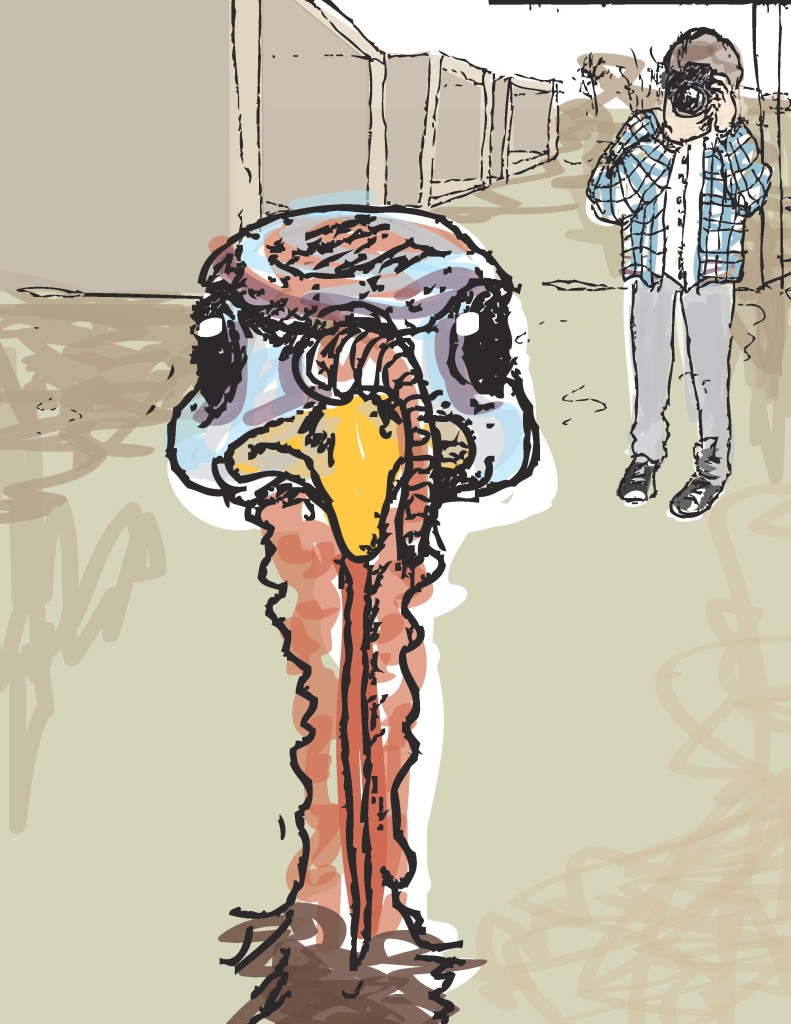

The wild turkeys of Marfa swept in off the plains, from the vast privately held ranch lands surrounding, and they were ugly, confident, and relaxed. Tens of miles in any direction to the next township, flatlands and mountains and moonrise in the rear of the photograph, room to spread out in the scorched waste of a decade-long drought. The turkeys traded it all for the easy life. Not exactly a full-scale plague of turkeys, just a half-dozen or so with bumblefoot and milkweed poisoning tottering onto the pavement at the edge of civilization. Now their prospects were fine. The turkeys would find a yard bordering on the scrub, take it easy for a few days, shit in mounds as big as fresh graves, and then, if relations with the landlord deteriorated, migrate with an imperious gait across the street to the next residence. They ignored legal crosswalks. They weren’t concerned about the ubiquity of the horseless carriage. They gorged themselves on lizards and hickory nuts and the cheese puffs that the Texans left behind after high school football spectaculars. They menaced the pre-school set with a particular vehemence. When they saw a toddler, they bore down on him clucking and squawking in that prehistoric way that tells us more about the velociraptor than it does about the main course of a national holiday repast.

The wild turkeys of Marfa swept in off the plains, from the vast privately held ranch lands surrounding, and they were ugly, confident, and relaxed. Tens of miles in any direction to the next township, flatlands and mountains and moonrise in the rear of the photograph, room to spread out in the scorched waste of a decade-long drought. The turkeys traded it all for the easy life. Not exactly a full-scale plague of turkeys, just a half-dozen or so with bumblefoot and milkweed poisoning tottering onto the pavement at the edge of civilization. Now their prospects were fine. The turkeys would find a yard bordering on the scrub, take it easy for a few days, shit in mounds as big as fresh graves, and then, if relations with the landlord deteriorated, migrate with an imperious gait across the street to the next residence. They ignored legal crosswalks. They weren’t concerned about the ubiquity of the horseless carriage. They gorged themselves on lizards and hickory nuts and the cheese puffs that the Texans left behind after high school football spectaculars. They menaced the pre-school set with a particular vehemence. When they saw a toddler, they bore down on him clucking and squawking in that prehistoric way that tells us more about the velociraptor than it does about the main course of a national holiday repast.

*

This account is concerned with the effect of the turkeys on their newfound neighbors. Let it be known: the politics of Marfa were tugged toward disparate power centers. In Marfa, there were the ranchers, with their inherited expanses, fallow and unused; the Chicano population, living out on the county road toward Alpine, in their faded trailers, quiet and imperturbable; and the out-of-town culture professionals, first attracted to Marfa because of the presence of large-scale site-specific works of minimalist sculpture—a disused army barracks gussied up with colored fluorescent bulbs and the like—and later by the presence of others of their kind. This last group was responsible for the sudden appearance of exotic terminologies in Marfa such as locally-sourced cuisine and restored vernacular architecture, the indigenous music of a strange, new tribe.

To each, the turkeys represented a unique local phenomenon. Each group interfaced with the turkeys (even perceived the turkeys) in a colorful and distinct fashion. The ranchers were used to inviting in the occasional red-state congressional delegate out for a weekend of liver punishment and buckshot dissemination, and if a turkey were to get got so be it. The ranchers did not come to understand a pestilence of the cheese-puff-eating and voluminously shitting turkeys until the turkeys began, episodically, to impede the free movement of pickups on the street called San Antonio. A certain turkey was nearly flattened out by the rail depot (now an interior design firm), and this constituted, in a tale of species interdependence, a turning point.

The following are names for turkeys in the Spanish language: pavo, pavo salvaje, idiota, turista, republicano, pistolero yahoo, Bautista hipócrita, blanquito, cerdo de comer filisteo, oligarca, pelele, retraso, culo-limpie. Each of these was occasionally employed when referring to the turkeys in the Mexican-American voting bloc, where the turkeys were understood to be avatars of the gringo oppressor, if not actual changelings. The Chicano community of Marfa did not attempt to run down the turkeys, feeling that to do so would subject their community to additional interference by the oppressor class, whether in the form of local constabulary, or state and/or federal agencies. The turkeys of Marfa certainly were hideous like many gringos—with their chaps, their melanomas, their tanned dentures, and their apocalyptic theologies. A late night comedy routine on someone’s porch in which the turkeys and the gringos were extensively compared would be highly entertaining.

Ranch owner-operator and Mexican-American. Despite class-related enmities fifty years in the making these groups came to agree on the necessity of the open season, a festival of downtown turkey assassination, also known as town statute number IY-2737, the Turkey Remediation Act of May 2012. It would be quick, it would be relatively painless, and it would demonstrate the benefits of responsible gun ownership. (High capacity magazines, however, were not in the spirit of IY-2737.) There might be bunting around city hall, country-and-western lamentations beneath a tent, awards and prizes, perhaps a pie-baking competition. Overhear, if you will, one speech on the subject delivered at the town hall meeting, We’re looking around in this town for some, uh, economic opportunity, there’s lots of people don’t have any kind of opportunity at all. Who’s to say that the opportunity couldn’t come from, uh, from these guys. Look at these birds—these are not attractive birds, really—these birds they, uh, don’t fly very well, they just endanger local folks by making a nuisance. Say you’re walking around, over to Lincoln Street, you see the birds, why you are liable to turn right around and head off a different direction. Even the mules on Austin they don’t like the turkeys, because the turkeys are always getting into their acreage, charging at the mules. These birds can bring additional tourism monies to our city, if we play our cards right. There’s no one around who’s going to defend these birds.

How wrong these words turned out to be. How wrong. The culture professionals of Marfa loved the turkeys. With a profane and unspeakable passion. Because the culture professionals loved all underdogs, loved the jackrabbits, loved the tumbleweeds piled up against the fences of the disused army barracks, loved the moment of driving in town when a drove of tumbleweeds rolled out before them, as if to bear welcome; the culture professionals loved the tarantulas of Marfa, loved the snakes, loved all the nuisances. They believed in a separatist nation of underdogs, all for the unreasonable purposes of art, which is human folly, which is monasticism, which is free jazz; they came to Marfa to defend the turkeys of Marfa, even should they need to lay down their own lives to do so. At the outset, their campaign on behalf of the turkeys was solemn, peaceable, tragicomic. At first they spoke their love only to one another, in whispers. Lee, who worked at the food truck, told Chelsea, who worked at the bookstore, and they were very nearly embarrassed about their partisanship. They loved the turkeys, despite the turkey fecal material, and they loved that if you happened upon them, you could whip out a camera and photograph them, and the turkeys would just stand there. They wouldn’t move at all. It is well-kown that Chelsea and Lee began their epic romance over their love for the turkeys.

Others soon joined the movement. Emancipate Marfa’s Turkeys (EMT) was born at the local Pacifica radio network affiliate, and this insurgent campaign numbered among its donors some of the most well-connected culture professionals in town, including a brace of curators who attended top-flight programs at Eastern universities, each of them with a wheat allergy and a piercing. In a complex of houses on the north side owned by a prominent southwestern philanthropic foundation, writers in temporary residence were busy composing elegies to the turkeys, who marched by their windows pridefully as if the north side constituted a nature preserve:

And so it came to pass:

Meleagris Gallopavo,

Of the Miocene;

Noble feathery

Interloper, pecking at

Modern drudgery!

Large wattles, it’s said,

Are correlated with good

Nutrition and

High testosterone.

Same as with the

African lapwing.

You, into the crepuscule!

Soon Marfa bloomed brilliantly into civic conflict. What is there to say about civic conflicts, but that they are as inevitable as moonrise, as inevitable as hoarfrost and deer tick, as inevitable as marsh gas and taxes, as inevitable as the diner cashier station and its shiny unblunted spindle. One group gets mad and calls the other varmints, bloodsuckers, cyanobacteria, one group holes up in a certain restaurant or at a certain roadhouse, inhaling paint fumes, invoking the gods, vowing never again, and soon there is no contact, even at softball games or at the farm stand.

Which was fine with the turkeys. The turkeys had figured the legislative process for what it was, the perfect way to immobilize a pest species competing with them for urban terrain. What can you say about homo sapiens sapiens and his ways? It was fine with the turkeys that the humans were distracted with pettiness, and in late spring they were cherrypicking slugs out by Frank Landry’s garden, sticking their heads under their wings for long uninterrupted naps, clucking contentedly. The sun was high, stoking the retributive drought, and the people of Marfa were all down at the public school bickering. A line of poults wobbled along behind the tom and hens, a promising next generation.

Meanwhile, in the craggy, unforgiving, boulder-strewn hills outside town, the mountain lions plotted their next move.

Rick Moody is an American novelist and short story writer best known for the 1994 novel The Ice Storm, a chronicle of the dissolution of two suburban Connecticut families over Thanksgiving weekend in 1973, which brought widespread acclaim, became a bestseller, and was made into a feature film of the same title. He has been regarded as a highly ambitious writer and one of the most original literary voices of his generation. Many of his works have been praised by fellow writers and critics alike, and in 1999 The New Yorker chose him as one of America’s most talented young writers, listing him on their “20 Writers for the 21st Century” list.