Kimberly Bussing

When we get home from Paris, we find that the house has flooded.

“I’m leaving you,” Gus says. “I was thinking about it in Paris, but now this feels like a sign.”

He’s just come up from the basement with his pants soaked to the knee. He is divorcing me because a pipe broke. I guess I always thought it would be a little more dramatic than this. I guess I always thought I deserved more of a flourish, an ending with more flair. But that’s how everything had been with him: thwarted expectations.

I tell him he can keep the house. In part because I have no fondness for it: Gus selected it and Gus paid for it and I did him the courtesy of smiling and saying it was a fine house indeed, even though he knew I was lying. I always repeat exactly what someone else has said when I’m lying. So when he smiled and said he was glad I thought so, too, he knew nothing I said was true. And so perhaps even then when we both were living in that house together as a married couple, we were just doing it because we liked the idea.

I also tell him he can keep the house because I hope one day he will turn on the faucets and remember the feeling of wading through the water in the basement and realize he has made a mistake.

Whenever Gus would leave for business trips, I would trash the house. Because he worked, I was expected to be domestic. His parents have been married since they were 21 and these are the roles they play, and Gus holds them up as models of success. Perhaps they are. Perhaps that’s the only way it can work.

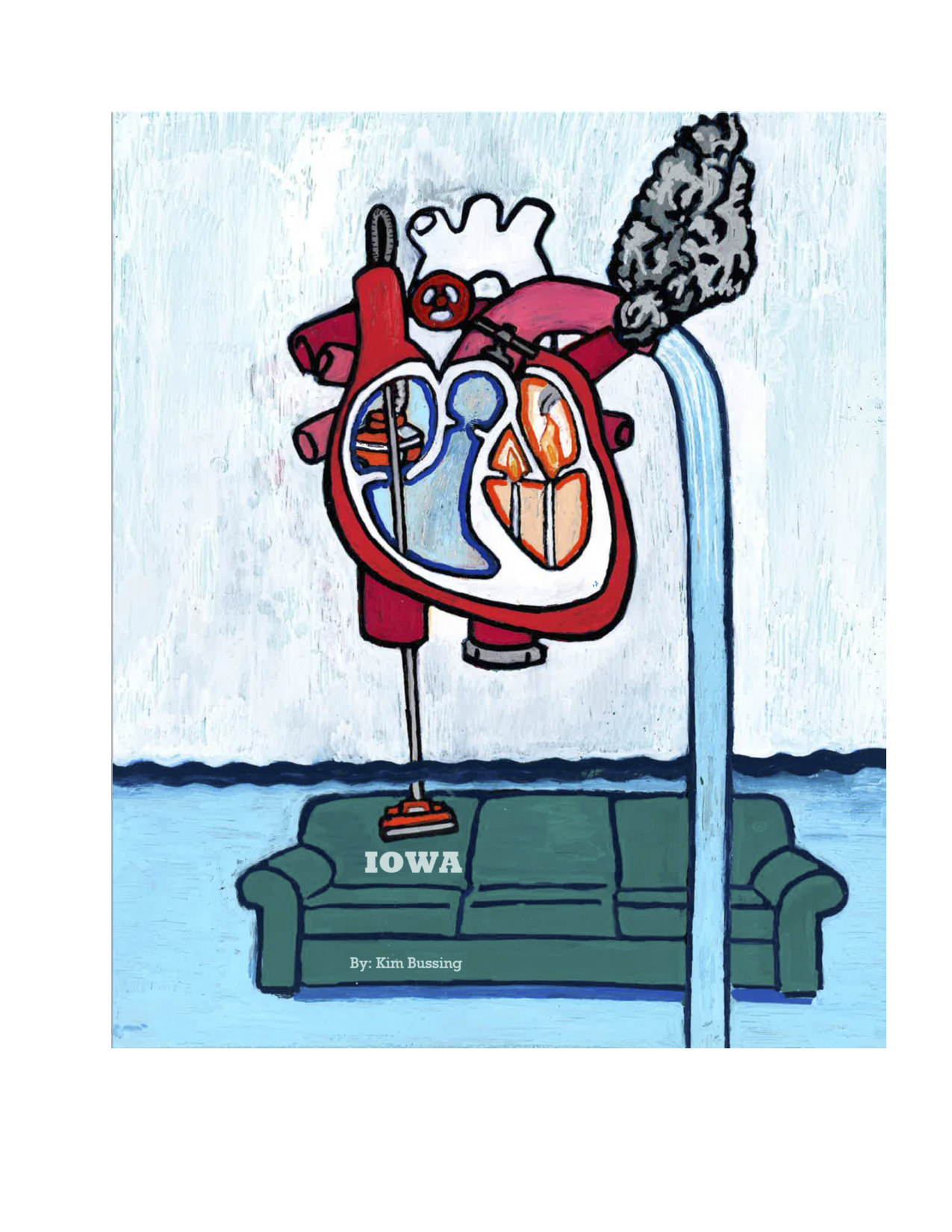

So I would do the chores in the morning and even set up a calendar that went something like this: vacuuming and changing the beds on Monday, Tuesdays were cleaning the living and dining rooms, Wednesdays were the bathrooms and vacuuming again, etc, etc. That was the general idea. But I also would buy cigarettes with cash and smoke them in the bathroom with the shower on and the window open because Gus despised them. He was a cardiovascular surgeon so he had good reasons and I could not counter fact with desire.

But with Gus gone, I would leave dishes piled in the sink. I would take showers and let the hair clump in the drain and walk around the house, trailing water behind me that would pool and seep into the wood floors. I would smoke in the kitchen and strew the ashes over the table like a trail of Hansel and Gretel’s breadcrumbs. Bring home library books and scatter them throughout the rooms with their spines cracked. Eat potato chips in handfuls on the couch so that there would be crumbs wedged between the cushions. Sometimes, depending on what it was like between us before he left, I would go to his study and pull all his binders down from the shelf. I would grab the pages and throw them in the air and watch them scatter over the room until you couldn’t see the floor. I used to think I might be depressed and thought about that for a few days but then figured it was too easy of a solution. A doctor’s note and a bottle of pills. It seemed too simple.

And then I’d vacuum and clean and reassemble so Gus came back to everything in its proper place.

Sometimes I would put a binder back out of order, just to see if he would say anything. I am still curious if he noticed, and if he noticed, what he thought.

My mother lives in Iowa and when she answers the door, she seems like she has been waiting for me. I imagine her sitting on her front porch, rocking back and forth, staring down the road that runs right past her windows as though my return was inevitable. When I arrive, it’s a Saturday and my mother looks anxious.

“You chose a pretty inconvenient time to come, Amy,” my mother says. “It’s Saturday.”

“I’m sorry, Ma,” I say, even though it seems at this instance, I should not be the one saying this. “I should have called.”

She stares at the suitcases I have behind me.

“More is coming,” I say. I don’t know why I’m justifying myself to her. Or if justification for her sake is the reason I’m saying this.

But more is coming. I had told Gus to pack everything that he didn’t want. I said I didn’t care what I got, but that he did. So he got to choose and the rest he would send to my mother’s house. I’m not exactly sure what will come here, but surely something will. There are a lot of clothes I left behind, and these stupid porcelain figurines I collected five years ago that I kept on a shelf in my closet. So Gus doesn’t need those, but of course he will remember that I had once regarded them as somewhat precious and during the aftermath of divorce it should occur to him that things that were once loved should be returned to their proper owner.

“So you’re back,” she says.

“Back in Bumfuck, Iowa,” I say.

She raises an eyebrow but doesn’t reply. It feels good, though, saying that. Bumfuck fucking Iowa. Fucking Gus. I would have been happy keeping things like they were. I was some shade of happy with him. Not everyone gets even that.

Saturday for my mother means the day before church. She is not a religious woman in any sense — I don’t think she has ever laid any claims to believing any religion — but she helps the reverend. On Saturday, she fixes his meals and goes over his sermons with him. She’s done this as long as I can remember, even back when it was a different reverend who for a while I thought was my father, although it turned out he could not have children.

My mother helps me in and takes my bags into the guest room. This used to be my bedroom, but my mother was quick to turn it over once I went to college. When I first married Gus, I thought it was my mother’s attempt to assist in severing my roots but now I am not so sure the room’s renovation was for me.

I am not sure why my mother is still here in this house, in this town, in Iowa. She teaches history a city over and there is nothing tying her to this place except perhaps a sense of loyalty. I always imagined she thought that if she moved, a mass exodus would abandon the town she had called home to ashes and dust. My mother straightens the sheets and leaves and comes back with towels and sets those on the bed as well.

“What happened?” my mother asks. Everything she is wearing is ironed. She is put together and the perfume dabbed on the smalls of her wrist, although freshly applied, is muted and proper. And here I am, with layers of stale sweat and airplane smell coating my skin. I want to tell her I look worse than I feel, but don’t want her to think that Amy doth protest too much.

“Marital difficulties,” I say. “I don’t know. The usual stuff. We drifted apart. Yada yada yada.”

“Weren’t you just in Paris?” she asks. She has moved to the kitchen and I follow her. She stands with her arms crossed. She is not expecting me for dinner, and since she is eating with the reverend, there is no food. I can see I’ve embarrassed her, catching her unprepared.

“We were,” I say. “But we’re not any more.”

Gus had been too excited for Paris. He had lifted me up and wrapped my legs around him and carried me to the bedroom. He had tickled my nose with the tickets. He hadn’t acted that way since we got married. So I had known something was wrong but I had gone along with it because I hadn’t wanted to waste something like that.

“I thought you weren’t coming back,” my mother says. “When you left for Bowdoin, you said you were never coming back.”

“I was wrong,” I say. “Now I just need some time.”

“I was hoping you weren’t coming back,” my mother says. “I love you, but I had hoped you would stay away.”

But she sets a place for me at the table and rummages through the cupboards. She grabs a box of cereal and pours it into a bowl, the pieces piling into the porcelain like a sigh.

The packages from Gus haven’t arrived. I email him again with my mother’s address, just in case he has forgotten, but still nothing shows up. During the week, she’s gone at the university and I read through the few books she has. There are old Stephen Kings and The Thorn Birds. Mainly, she just reads the Bible.

“You’ve converted,” I tell her on Thursday. She is sitting in the living room and I am lying on the sofa, staring at a spider that is crawling across the ceiling. There always seemed to be spiders in the corner of this wall in this house, and often I would watch them as you would watch an enemy, but now I watch it because it seems like what I should do. There’s something so tangible about childhood nostalgia that I could choke on it.

I do not prefer this to Gus’s house, nor do I prefer Gus’s house to this. They are too different to compare. I am not at home in either one of them, for that matter, because both seem like different variations of the same thing. Which is to say that they are both rest stops, although I’m not sure to where.

“And you’re divorced,” my mother says.

“You’re wrong,” I say. “We’re not divorced yet.”

“You’re wrong, too,” my mother says. “I’m not converted.”

She hasn’t asked anymore about why I’m back. She never got married. She never thought that kind of thing would take for her, and she thought that about me, too. For someone who claims to be agonistic, she has a fatalistic view of destiny.

I point at the Bible, which she is holding. “My whole life you’ve never read it.”

She shrugs.

“Well,” she says. “Do I really need to be telling you that things change?”

“Why now?”

“Well, maybe, Amy,” my mother says. “Maybe I would like to get what all the fuss is about. Maybe it wouldn’t hurt you to go searching after some faith, too.”

“I’m sorry,” I say, because she seems agitated. She returns to reading the Bible and doesn’t look at me. I light a cigarette and my mother doesn’t complain. When I lower it from my lips, she reaches out her hands and takes it and inhales once and then passes it back. The entire time she does not look back at me. Her eyes are trained on the Bible.

Gus had not believed in God either. Once I had suggested we go to church on Christmas Eve, and he had yelled one of the only times I had heard him yell. He thought church a personal insult, like someone found his way of living so detestable, they had to set out and correct it. Those were his words. He found priests preaching on predestination and fate and heaven to be directly attacking him. As a surgeon, he could not walk into a church and be confronted with mortality without being reminded of the patients he had saved on the operating table and that despite his efforts, they would still, another time, die. It reduced him to just a doctor. But he was a man of science with the same vigor and adamancy of cultists or Scientologists howling on street corners.

It’s always seemed to me that people are either driven by faith or by a lack of it, although the hearts of both views look almost indistinguishable, when you stare at them closely enough.

For the record, I am Christian. I was exhausted by both extremes and thought I would just be better off in the middle. Although I was never much good at it. I cannot remember the last time I prayed.

“What are you doing?” my mother asks.

“I am waiting for my packages,” I say, although at this moment the waiting is paused. The mail has come today and there was no FedEx truck, either, crawling over the road my mother no longer has a reason to watch.

We are in our usual spots. I am craning my neck to find the spider, but tonight it has disappeared into the recesses of the house. There is a tickle of betrayal at the back of my throat.

“But after that?” My mother says.

“I thought I’d figure it out then,” I say.

My mother puts down the Bible on her lap. As she speaks, she taps the page with her thumb. With the fervor she attacks the Bible every evening, I expect her to quote it to me. At first I waited with annoyance, but now the anticipation has built so that I am curious what she would say. But she recites nothing from it, as if she is reading it but doesn’t know it at all.

She tells me that sometimes she forgets how young I am, and I remind her that I’m 28. That is not that young, relatively. I have lived my own life for ten years outside of this place. A decade is a large space — think how many births and deaths and snowfalls and petals unfurling have occurred in such a wide expanse of time.

“What do you want to do?” my mother asks. “Why are you back here?”

I rest my lips on the arm of the sofa. The fabric is pressed against my mouth and suffocates me. It tastes of dust.

“That’s personal,” I finally say, and my mother shakes her head.

“You’re going to put too much hope in this place,” my mother says. “Don’t do that. Stop putting faith where it doesn’t belong. Look where it’s got you.”

And she gestures around the room like she’s ashamed that I am in it.

Later, at night, I sit on her front porch and smoke one cigarette and then another, and then another, until I am surrounded by the stubs, and ashes. I realize I’ve finished the pack but it’s gotten too late and I’m too tired so I will wait until the morning to get another.

I sprinkle some of the ash onto the fine hair of my arms. This pack I had bought at Charles de Gaulle Airport, when Gus was in the bathroom and I had said I would go and find coffee. I blow the ashes away and then immediately regret it. I cup the air in front of me like I can recapture them, but they are gone. Not that it matters. I would never be able to get all of them. It would never be able to be like it was.

I have a memory of when I was quite young, standing in my cousin’s backyard. As I recall, they lived against the woods, their property spilling out into a mess of pine trees and blackberry bushes and underbrush that if you went deep enough into, you could turn in all directions and think you’d gone back in time, before anyone had ever discovered how to carve up a log and make a building in the first place.

It had been summer and was getting late, and three of us were sitting just a ways out of view of the house. Night was settling above us in a tender way, with the air still warm and violet light seeping between needles and scattering over our feet. You could hear crickets rustling and in those few moments there was a sense of timelessness. I had wished we could stay there forever, captured, it seemed to me, amidst a great beauty and profundity you can only find when things are so dark and so still.

The more I think about it, though, the more I am not sure if it was a memory. There are some things I look back on and realize never happened, that I had dreamt them or invented them. I know this because when I look closely, they’re too exquisite. I had just placed them there, to be remembered, to make things somehow more precious.

Which makes it worse, when I realize that, since it makes the past as unclear and uncertain to me as the future.

I only think of this now because that was how things were with Gus. I often wonder if I have fabricated so much of what happened, if there was not nearly as much goodness between us as I can remember, standing at my mother’s living room window and waiting for the packages to come.

But I cannot bring myself to call him to ask.

My mother is surprised when I ask if I can join her for church. The last time I went was when I was baptized eighteen years ago and my mother never asked me to join her again, after that.

“If I ask you to go to church anymore,” she had said, “I worry that you’ll lose your religion.”

But I sit in the passenger side of the car as she drives to the small, white-steepled building, which is the nicest building in town. She arrives early, to help the reverend, and I sit in the pews by myself as my mother sets out coffee and paper cups, and the reverend ruffles through loose-leaf paper and clears his throat. My mother’s reverend holds the services at night. There was some reason for this, my mother once told me, but I have forgotten it because it did not seem relevant at the time. The entire phone call had been peppered with too many “Gods” and “Lords” and then, Gus and I were freshly married and I had been listening to her while watching him mow the lawn and imagining how his lips would taste of grass and dew.

As soon as the service begins, I drop to my knees and rest my head on the bench in front of me and close my eyes. I sit through the entire service like that. My mother nudges me when people sing or stand but I stay kneeling there, with my eyes closed. Perhaps people will think I’m praying and think highly of me.

My mother’s church has begun a tradition of lighting candles at the end of the service. My mother walks around, passing out thin candlesticks with cardboard wrapped around the middle to catch wax, and she lights the pastor’s candle, and he lights the person closest to them, and then they light the candle of the person beside them, and so on. When the last one is lighted, the congregation lines up and walks forward and places their candles in a display the pastor has set up at the base of a cross.

I do not take a candle when my mother passes them out and when the first person in my row gets their candle lit, I stand up and move to the side. I watch as people wade through the darkness with their candles, depositing them with the others until what has been created is a giant, flickering beacon.

It is beautiful but I do not understand why. All it is are fragments of flame captured to be examined up close, made so vulnerable as to be at the mercy of a protracted sigh.

But the people flock to it and once they’ve deposited their candles, there’s nothing for any of us to look at in the darkness but the cross, and none of us can look away.

When the service is over I excuse myself from my mother to go to the bathroom and splash cold water on my face and look in the mirror, but still I feel the way I might have felt if I spent the evening at the grocery store. Nothing within me has been unsettled, or changed. I keep the water running and stare at my fingers under it. I am surprised to find I’m still wearing my wedding ring.

I go back and the church has mostly emptied out except for the few people who have returned to the pews to drop to their knees in some degree of privacy.

I pick up one of the candles and hold it close to my face. The heat from the flame is minimal but it creeps over my skin and I briefly wonder how it would feel against my lips. But I’m afraid to risk extinguishing it. I’m afraid of the darkness caused by losing even this one light.

# #

Originally from Seattle, Wa, Kim Bussing is currently in Georgetown University’s Honors English program and previously studied creative writing at Pembroke College, Cambridge University. When not writing, she can be found at a used bookstore, drinking too much coffee, or on Twitter: @kimbussing.