Anabel Graff

I am a twin. We were born on the same day but at different times—I came out before dinner, and she came out after. My dad got two tax cuts. We were born approximately one hour and forty-seven minutes apart on an early spring day in March. When my mother first held my sister, she pooped in my mother’s hand. I guess this made her a troublemaker.

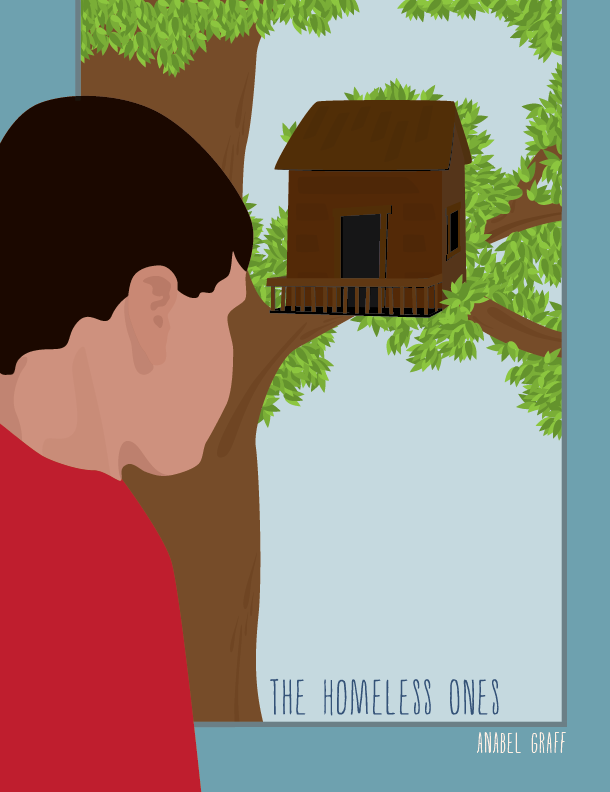

I have my boy things and Sylvie has her girl things. My boy things include two soccer balls and a baseball bat. I also have a 1977 Tim Raines baseball card that my dad gave me that’s worth a lot of money. It’s from when he was first drafted to the Expos. In our backyard, we have a tree house. My dad built it for us a few summers ago and I helped him out with it. It was cool to pick out the wood and use a hammer. He sweated the entire time and took the lord’s name in vain when he missed the nail and hit his hand. He let me have a sip of his beer when we finished, and when my sister wanted to paint the tree house pink, he didn’t let her, and I appreciated it. My sister is not easy to say no to.

The tree house is a wonderful thing. It has two windows, a door, and a rope ladder that reaches the ground. It isn’t very high up in the tree, but you still have to swing yourself up the ladder to get to it. It’s tricky to climb at first, but then you get the hang of it. The door opens and closes, just like a real door, and the windows do too. It is perfectly balanced on a branch.

When we first built it, my sister and I took turns inside. We marked on a calendar what days were mine and what days were hers with fat red and green Xs. Sometimes my friends from school came and had sleepovers. Other times I took my baseball cards up and reorganized them according to different principles. One time I arranged them alphabetically, another time chronologically. One time I even did it by geographical location. Tim Raines always led off, though.

On Sylvie’s days in the tree house, I watched her play from my room. I could see the tree house, and my sister, from a window above my bed. When Sylvie played in the tree house, it became a bird’s nest on a ship, or a cabin stowed away in the woods. Sometimes she let me join in and told me to gather sticks for winter fires or bring out orange juice for the sailors who had scurvy. Other times she made me do things I didn’t want to do. Like when she told me to jump off the ledge to save Dodge the deck-swabber. When I said “no” and looked at her, I could tell she thought about pushing me. All she did was chew her bottom lip, but she didn’t need to say anything. I never really went back to the tree house after that. My sister has imaginary friends, and Dodge was only one of them.

When we were little, when we were babies, my mother said that we used to whisper secrets to one another.

“You were inseparable,” she told me while looking over some legal briefs for work. Her brow was wrinkled and she had her papers all over the kitchen table. There was a take-out container of Lo Mein on the table. She had missed dinner again; it must have been the third time that week. My father hadn’t even gotten home yet. “Everywhere she went, you went,” my mother said distractedly. “When Sylvie started walking, you ran to catch up to her.” She had told me this story many times before.

We had our own language, she told me, even though we couldn’t really speak English or anything. We would whisper secrets to each other, and we were the only ones who understood. I don’t remember this exactly, but I know that we used to be best friends. We didn’t need to say it, but I knew, and Sylvie knew, that we understood one another in a way that you couldn’t put into words. But then we went to school, and the imaginary friends started coming, and instead of whispering things to me, she would whisper things to them.

The first imaginary friend I can remember actually liking was Bobo. Really, I guess, he was the first friend that Sylvie allowed to like me. Bobo was an elephant and didn’t seem to be choosy in terms of friends. That was when Sylvie was pretending we had run away to the circus. My sister, the ringmaster, would put on a red dress she had worn for a Christmas party a couple years ago. It was too small for her now, but she looked the part. She had found a skinny twig in the backyard, and she used it like a whip to direct us performers. I would be ready off-stage with my soccer ball. She would signal with the twig, like a conductor, and then I would show off my moves. I’d step in front of her mirrored closet, onto the stage. She would go over to the cassette player and play something with a lot of cymbals. I don’t remember what the tape was, but I remember the sound it made as it got started up, warped and crippled. And then there was my cue.

“Now, Tommy!” she whispered angrily, then took the twig and sliced the air, hitting me on the arm. A hot, angry line formed where her stick had hit me. It stung like a thousand bees.

“Ow! Why’d you have to do that?”

“Perform or I will take away your peanuts.” Her curly hair moved with her as she stomped her foot and placed her hands on her hips.

“I don’t even like peanuts. Bobo is the one who wants the peanuts, not me. He’s the elephant.” I motioned to the invisible elephant that was supposed to be standing off stage. Bobo was the big finale. According to my sister, he was a very good elephant, rescued from the jungles of India. He had traveled very far to reach our house in Middletown, New Jersey. He needed somewhere to say. She said he had nowhere else to go. According to my sister, he could paint, sing, and dance better than any human being she had ever met. I, of course, had never seen any of Bobo’s talents.

“And now, the amazingly-super-talented-dexterously-magnificent-Bobo-the elephant who will dazzle you with his superior talents!” She twirled around, holding her twig. “Tommy, move.”

I grabbed my soccer ball and moved away from the mirror, where Bobo was now supposedly taking center stage.

“Tommy, you are standing in Bobo’s way,” said my sister.

“Well, how am I supposed to know? I don’t see any elephants.”

My sister stomped her feet. “But you can hear them, right?”

“Sylvie, that’s just you.”

“No, it isn’t.”

“Yes, it is.”

“No. It’s not.”

“He’s not real. You’re a liar.” She hated being called a liar. My parents thought she was a liar.

During that summer before school started, she had to go see a doctor because she lied so much. My sister had been stealing things from my mother—lipstick, dollar bills from her purse, breath mints—and hoarding them under her bed. Our mother had confronted her when she’d returned, late again, from work: “Sylvie, why did you take my things? Don’t we buy you everything you need?”

She had pouted, and her lips and cheeks were as red as that ugly velvet dress. “I didn’t take anything.”

“Sylvie, don’t be rude,” my mother answered. “Why did you take them?”

“I didn’t take them. Someone else did.”

I knew where this was going. Dodge was the first, but between Dodge and Bobo, there had been many, many friends. We didn’t all get along. Flo, her marine biologist companion, and I just didn’t see eye to eye. Flo (and my sister) wanted me to eat sardines to taste the sea, which I thought was pretty gross. I also did not get along with Klaus the sad German clown or Billy her friend from the Wild West and especially not Tatiana the Russian prima ballerina (she wanted me to wear tights). And Sylvie only introduced me to some of them. Maybe only when she needed me to play along.

“Who?” my mother asked.

“Mom, I can’t tell you who took them. Look, it wasn’t me. It was someone else. I saw them do it.” She looked down at her feet, determined not to meet my mother’s eyes.

“Sylvie, don’t lie.” My mother stared at Sylvie. “Look at me,” she said. “Why can’t you be good, like your brother?”

Sylvie’s face turned even redder. I felt guilty even though I hadn’t done anything. I didn’t want to be there, watching Sylvie’s interrogation.

“I am not my brother and I am not a liar!” She paused and chewed her lip, looking like she was mulling something over. “Penelope did it.”

I knew who Penelope was. That summer, we had spent almost every afternoon at the pool, and Sylvie had tried to introduce me to Penelope earlier that day. I felt my stomach do this weird thing, like it was falling out of my body, like if I looked down I would see it in a bloody mess on the carpet between my feet. I always felt like I was stuck in the middle of everything—of my Sylvie and her imaginary friends, of Sylvie and my parents. I didn’t know who I was supposed to be loyal to. She was my twin but never let me be hers.

At the pool, I played with the other kids from school, rounds of Marco Polo and chicken fights. All I wanted to do was play with her. But she didn’t want to play with me. I still asked her to join. She would just shake her head and go to the deep end, laughing and splashing by herself. Instead, I would play with the kids from school. We’d get into wars with water guns or we would be pirates or sailors on a submarine. We would play make-believe together.

“Tommy,” Robert Henderson said. “Your sister is so weird. Look at her.” Robert Henderson was a weird kid himself. He ate glue and picked his nose when he thought no one was looking. But between third and fourth grade he had grown a lot and gone to baseball camp, and suddenly everyone thought he was cool.

“No she isn’t.” I said. “She just likes to play by herself.”

“Whatever, she’s a weirdo.” He jumped out of the pool and picked up a water gun. He kneeled down on the hot pavement and aimed it at my sister. “Sylvie the Strange. That’s what we’ll call her. And you guys are related. So you’re a weirdo too.”

“Shut up,” I said, knocking the water gun out of his hand.

“Watch it,” he said, while his wet hands grabbed my shoulders and threw me into the pool.

Sylvie didn’t notice anything and I hated her for it. She swam up to me, happy as a clam. She didn’t see me trying to catch my breath, treading in the water.

“Tommy,” she said. “I want to introduce you to Penelope.”

“Shut up,” I said. Then I splashed her with as much water as I could, and I felt my foot make contact with her body as I kicked to get as far away from her as possible.

Looking down at the carpet of the hallway, I felt bad about how I had acted earlier that day. But Sylvie made it hard on purpose. She hadn’t talked to me since we got home from the pool.

“Does Penelope go to school with you?” My mother turned to look at me. “Should I call her mother?”

I shrugged.

“Her mother is dead. She drowned,” my sister said, deadpan.

This caught my mother off-guard. She felt bad, I could tell. Her stare had softened. “Well, should I call her father?”

“He’s dead too,” my sister said without skipping a beat.

“This is ridiculous!” my mother exclaimed. “Who is this girl?”

“She’s not a girl, Mother. She’s a mermaid.”

That night, after my mother had yelled at Sylvie about the stolen stuff and sent her to her room, my mother pulled out a pair of old goggles from her bathroom. They were bright green and tinted yellow and one of the straps was a bit torn. She told me to take the goggles to the pool next time so the chlorine wouldn’t make my eyes so red. I didn’t tell her that it wasn’t the chlorine.

Calling my sister a liar was the only way to get through to her, you see? Standing in front of the three-way mirror in her room, I could see her cheeks flaming from all angles.

“Bobo left and it’s all your fault. He’s run away, you made him run away like all the others.” She jumped on me.

“I did not make Bobo run away.” I threw my sister off and she hit her head against the mirror. It swayed and shook from the crash but did not break.

“Just leave! I’m going to tell Mom.”

“No, you won’t,” I said. “No you won’t. I’ll tell her you are lying. Because you are a liar.”

“I’m not.” She was crying big, fat tears that left dark spots on her velvet dress.

That’s the thing about sisters. Especially twin sisters. You know how to make them feel bad, but then it makes you feel bad that you made them feel bad. And then you feel guilty about it. But I don’t know if that feeling was worse than the feeling I got in my chest each time another imaginary friend came to stay, when she chose another friend over me. It burned, and even if I drank water or took some Pepto-Bismol and let it run down my throat, down towards my heart, it still hurt. I know I’m too young to have indigestion, so I don’t know what it is.

* * *

Bobo was one of the last imaginary friends I was introduced to, and that was a while ago. My sister doesn’t have many friends at school. We’re just finishing 5th grade at Middletown Middle School. My sister still has to go see the doctor, but I don’t have to go. We are the only twins in our class. We don’t really look alike. My sister has blonde hair and is very pink, and when she gets mad, she gets very, very pink. She looks like my father, but I look like my mother. We both have freckles. She likes to be in charge.

We have an assignment that we are supposed to read aloud today. It is for Language Arts. Our teacher, Mr. Doppler, is kind of weird. He gets very excited about class, and books, and when he reads aloud to us, he spits a lot. Right now we are reading The Secret Garden. It’s a girl book. It’s about a girl named Mary who finds this garden. Some people in the beginning thought she made it up, but really she didn’t. They go to the garden, the kids in the book, and they change.

Mr. Doppler is reading aloud and spitting out the words: “Where you tend a rose, my lad, a thistle cannot grow.” He holds the book up and moves quickly around the classroom. “And what do you think that means—” He pauses and scans the room, spinning around, until he lands on someone, my sister, who isn’t paying attention. “Sylvia, what do you think it means? Sylvia? Are you with us?”

I try not to be embarrassed for my sister. My palms sweat just thinking about it. My parents do not like my sister’s imagination. They don’t like it so much that now my sister has to see the doctor twice a week. I tried to ask her about it once, but she pretended she couldn’t hear me.

“Sylvie,” I tried to tell her, when she came back from the doctor one time. “You can talk to me about it. But she wasn’t listening. She was lying on her bed, with an atlas in her hand. Her room was plastered with posters of dinosaurs, her latest obsession.

“What’s that you said, Dr. Gustovitz?” There was silence in the room—it was as quiet as the frozen dinosaurs must have been in the ice age. She flipped through several pages of the atlas. “But, that’s impossible! Really, a Tyrannosaurus Rex?”

“Sylvie, you can talk to me,” I tried again.

“Dr. Gustovitz, I think, yes, I think it might just work! With your knowledge about the prehistoric rituals of dinosaurs, and my idea… yes!” She slammed the atlas shut and then walked over to where I was standing in the doorway and slammed the door.

Later that night, my sister must have thought I was sleeping. She crept in very quietly. It is hard for my sister to be quiet. She whispered straight in my ear: “He asked all these questions. More questions than I ever could think of. Why did I make up the people? Was I alone? Did I feel lonely? Did I think I needed more friends? Did I like to read? Watch TV? Did I play with dolls? Did I hear voices? He asked me where they went, and where they came from. I told them I had to be their friend because they had nowhere else to go. They didn’t have another home, I said to the doctor. He told me if I tried to make friends, the imaginary ones wouldn’t come anymore. He told me if I tried… he asked me how I felt about you. I said…”

But she never finished her thought, or maybe she did, but I really was asleep. I don’t think I imagined her hot breath in my ear, or the stinging sound her words left in it.

“Sylvia,” Mr. Doppler says again.

She looks up. “Sorry, I was doing something else.”

“Oh,” Mr. Doppler says. “I see.” He frowns. “You were away in your own secret garden.”

The class laughs.

I want to step in and save my sister. I could just answer the question for her, and Mr. Doppler would stop bothering Sylvie. I hate her for doing this. I interrupt without raising my hand.

“The part you read has to do with the kids. About thinking good thoughts. If you try hard enough to think good thoughts, the book says that good things will happen.”

“Yes! Thank you, Thomas,” Mr. Doppler says.

“Yes, thank you Thomas,” my sister mouths, even though she doesn’t mean it. Then she chews her lip and peels off the dead skin with her teeth.

At the dinner table my family is eating together for once. We are eating chicken. My sister does not eat it and I don’t either. One time, in science class, we dissected a chicken wing. Dissecting was like having dinner, cutting with strange tools, but instead it smelled bad and we didn’t get to eat it. Sylvie was not my lab partner, but a boy I played soccer with named Lance. He pointed out the muscles and the ligaments, and now I have a hard time swallowing chicken without thinking about birds flapping their wings, and sometimes it tastes fuzzy like feathers are caught in my throat. My sister is not eating the chicken, like me, but it’s not because of dissections.

“Why aren’t you eating anything, Sylvie?” my father asks. He has taken off his tie but is still wearing his white shirt and jacket. Someday I will wear a jacket to dinner too, when I have my own family.

“I can’t eat this chicken,” Sylvie says.

“And why is that?” my mother asks.

“Because Kevin can’t eat this chicken.” She swings her legs and says this because she thinks it is a completely good reason not to eat the dinner my mother has prepared. My sister likes to be difficult, and it makes my parents upset.

My father stops eating his chicken wing. It does not fly anymore, this wing, it just drops down, and makes a heavy sound. “Sylvie, not again. Not another one.”

“Oh, he’s not another one,” she says. She knows they are referring to her imaginary friends.

“He’s not?” my mother asks.

“No. He is a great friend. He used to be an investment banker in New York. He taught me how to read the stock market.” Sylvie is smiling.

“Sylvia Constance Babin. Do not lie to your mother.”

“I’m not lying,” Sylvie says. “He’s in the tree house.”

“Sylvia. It’s enough already. There are plenty of kids in your class you can hang out with.” And then my father adds, “And you’ve always had your brother to be your friend. Can’t you hang out with him?”

I feel hot and uncomfortable because I have already realized that my sister and I are not friends and will never be friends, even though we are brother and sister, even though we are twins.

“Do we need to make more appointments for the doctor?” my father adds. My sister looks sour, like she has tasted something she doesn’t like at all.

My mother looks to me now. “Thomas, do you know Kevin?”

I think for a moment. “No,” I say, and look to my sister. She is getting pinker and her eyes are watery. “No,” I say again, and I wonder whether I will save her from my parents’ yelling or if I will try to hurt her like she hurts me. Then the right words come and I look down: “We have not yet been introduced.”

She does not talk to me for days or come to my room to whisper the truth. She does not talk to my mother or my father. They have made her see the doctor every day after school. They even bother to take her there themselves, alternating days on a schedule like me and Sylvie used to do in the tree house. She goes from her room to school, to the doctor, to the backyard, to the tree house. I watch her take things out there: a pillow, a blanket, cans of soup, matches, toilet paper. I wonder if she is planning to run away, like so many of her imaginary friends did. When my sister is out at the doctor’s, I go to our backyard and climb up the rope ladder to look inside our tree house. It is cluttered with things, but no one is in there. It smells like dirt, like the backyard. She does not know that I went there and when she comes back home, angrier and pinker than usual, I keep it a secret.

But more things start disappearing from the house. My baseball cards, even Tim Raines. I look all over my room, but I just can’t find it. One of my soccer balls is gone too, and so are most of my socks. Other things are missing—spoons and bowls from the kitchen, books from shelves, my copy of The Secret Garden, my sister’s rug from her room. In my bathroom my toothpaste is gone and so is my toothbrush. My soap is not where I left it. It also smells different in there, like an animal or something. Something wet and dirty. I am the only one who notices.

I go downstairs to try to find my book. I pass my father’s office. We are not supposed to go in there but the door is open. Sylvie is inside. Her back is towards me.

“Sylvie?”

She jumps. “Tommy, you scared me!”

“What are you doing?”

“I’m trying to find Dad’s cigar box. Kevin wanted one.” She continues to search our dad’s office. There are papers everywhere and pictures of him with important people covering every surface. One time he met the prime minister of Canada. In the picture my father is smiling and shaking his hand.

“Sylvie, why were you in my bathroom?”

She closes a drawer she is opening. “Thomas, I wasn’t in your bathroom. Kevin was. Can you just help me?”

“I don’t want to,” I say, but I don’t know if it’s because I don’t or because I want to hurt her. Maybe it’s a little of both. I know where he keeps his cigars, but I don’t tell her where they are. Instead I ask, “Have you seen my copy of The Secret Garden? I need it for the assignment.”

“Oh, yeah. Kevin wanted to read it. It was one of his favorite books in school. He is so smart. You wouldn’t believe how smart he is, Tommy. Smarter than Dad.” She moves around the office until she finds the big wooden box.

“Ah-hah!” she exclaims. “This is great. Kevin said it reminds him of the good old days.” She walks towards me, but I don’t let her by.

“Sylvie,” I say. “Why are you taking all my stuff? Can you give it back?”

She pouts. “It’s not for me, Thomas. It’s for Kevin; he needs them. He lost everything in the recession. You know how to share. We have to share with him.”

“Stop making things up.”

“Why don’t you believe me?”

“Why should I?” I know these words will hurt her. “I’ll tell Mom and Dad. They’ll make you bring it all back.”

She looks down. “Please,” she says.

“Why do you need to be friends with these people? Can’t you just be my friend?” My palms are sweaty again, and I feel that weird feeling I get in my chest whenever I am around my sister.

She doesn’t say anything for a minute. “I can’t. You just don’t understand.”

“Yes,” I say. “I think I do.”

“You can meet him. Do you want to meet him?” Her eyes beg me. “You would like him. He said he’s going to take me to Disney World. Wouldn’t you like to go with us? We would have so much fun.”

“No,” I say. “I don’t. I don’t want to meet any more of them. I don’t want to go to Disney World. I don’t want to go anywhere with you.”

And then I walk back to my room, leaving her with her stash.

In the middle of the night, I hear a noise. At first I think my parents are home from the party, but the noise is coming from my sister’s room. Things are moving, and I hear footsteps. I want to go out and check on my sister, but that would be breaking my resolve. I go anyway.

My feet are cold on the wood floor, and she is there, rifling through her room. “Sylvia,” I say. “Where are you going?”

She turns around. She is holding her red velvet dress. “It’s not about you, Thomas.”

“Is it always about you, Sylvie?”

She looks away. “Don’t you want me to be happy?”

“Can’t you just be good?” I ask without answering her question.

“I’m trying,” she says. “I am trying. I try so hard, but it doesn’t work.”

“Can’t you just ignore them, the imaginary people?” My palms are sweating so much that I feel like I’ve been swimming.

“How many times do I have to tell you that he’s real, Thomas. Kevin is real. I’m not making it up! “

I look at the floor, I look anywhere but her face. “Can’t you at least give me my Tim Raines card back?” I ask. “You can keep all the other stuff.”

“I have to go.” She takes her backpack and begins to leave the room.

“I’ll call Mom and Dad. They’ll make you stay.” I go over to the phone in the hallway between our rooms and pick it up. The dial tone echoes in the room, but then I hang up. “Don’t you want to be my twin anymore?”

“I think…” she says, obviously thinking hard. She is chewing her lip like she does and is trying to find the best excuse. “That you are a rose, and I am a thistle.” And then she leaves.

She is gone before I can give her my version of the story. I say aloud, even though she has left, “And I think that you are a rose and I am a thistle, and that is what makes us twins.” Without my sister I am lost and without a home, just like her imaginary friends.

I go back to my room and look out the window. I see my sister in the yard, a blob with her backpack in the moonlight. She walks towards the tree house and shakes the ladder. She waits for a moment and from my room I see a man climb down. He takes my sister’s backpack and picks her up, carrying her on his shoulders like a princess. He is clutching a dirty pillowcase full of things, full of my things. I can’t look anymore because my eyes are blurry so instead I lay on my bed, waiting, praying that this is a dream and soon my sister will come into my room to whisper the truth. But I don’t hear any footsteps outside or creaks on the stairs. All I hear is the sound of a car starting and the screech as it pulls away from our quiet street.

Anabel Graff received her BA from Vassar College and her MFA in Creative Writing from Texas State University. She is the winner of the 2014 Prada Feltrinelli Prize and The Fiction Desk’s 2015 Ghost Story Competition. Her work has appeared or is forthcoming in Day One, Prada Journal, Joyland, Printer’s Row and The Fiction Desk. She lives in Sag Harbor, New York, where she teaches creative writing and is at work on her first novel.