John Thurgood

1.

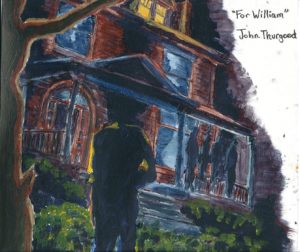

The first real girlfriend William ever had was Vevay, which could have counted as his first real mistake, too, because we were pretty sure she was cursed. From the moment Vevay Hollander moved to our neighborhood, the rest of us knew to be afraid of her. She lived at the dead end of Negley Avenue in the biggest and most ornate house on the block. The house was haunted, and Johnny Yu’s older brother had told us that the family who lived there before Vevay had hanged themselves off the back porch, the whole family strung up in a row. Sometimes, at night, we would huddle behind the big oak tree at the edge of her property, hiding in the oversized roots—it was the closest we would dare after dark—and would stare into their backyard for a glimpse of the family’s tormented spirits, doomed for all eternity to swing under the punky timber of that old porch.

But we never saw anything.

An East Coast developer had built our subdivision in the 70s and laid claim to the back lot to raise his family. He was the one who had crafted that ridiculous house, sparing no expense. As kids, we wondered about the trick bookshelves and hidden passageways inside and the mischief for which they were designed. It was said that upon moving in, the man had four kids—two boys and two girls—and a wife, who was pregnant.

The boys were oldest and mean. They bullied the other kids on the block, as well as their younger sisters, and made those girls do despicable things in the woods behind their house. We had always looked for the latent signs of their work, as if malice could be locked away in the bark of an oak tree or the smell of honeysuckle along the creek. We imagined the rituals they performed: dancing around fires, reciting demonic phrases, marking the sisters with cryptic seals.

The youngest sister was said to have been murdered, and we knew the spot where it would have happened. There was a small clearing in the gully, down from the big house. Nothing grew there. The dirt was hard and cracked. Tiny fissures moved from the middle as if the ground were slowly widening. Johnny Yu’s brother had said that it was widening for another sacrifice, and that it happened every twenty years. We figured he was lying. The cracks were probably caused by a sewage pipe, heating and drying the earth.

But still, others said it was the baby girl, weeks after she was born, who had been given to the earth, a jealous display of sibling in-fighting led by the two oldest, the brothers, and that was why it was slowly opening again, because the soul of the child, upon reaching its twenty-first birthday, would climb from the craggy dirt and take vengeance on all the callous boys in the neighborhood.

When Vevay Hollander moved into the house, she had been the youngest child to a sister and two older brothers. We couldn’t say when most of those stories became common knowledge, but the arrival of Vevay and her family had solidified the fact that the house at the end of Negley Avenue was haunted—whoever lived there harbingered death. That was why the moment we discovered Vevay Hollander to be pregnant, we knew the myth of our neighborhood had come true.

2.

In the hospital, no one wanted to say what we already knew. We pushed our way through the big double doors and into the emergency ward, where Ben Pall lay half-conscious on a gurney. Broken glass peppered the skin around his baby face. He was a year younger than the rest of us, and his slight frame and round cheeks pegged him as much younger. His hair was splayed, as if mussed by margarine, and his shirt had been cut away, revealing the skin around his bony ribs, squeezed and puffy.

A nurse stopped us. She said we weren’t allowed in the ward if we weren’t direct relatives, but we ignored her.

“Where’s William?” Debby Hohensinner asked.

Ben only mumbled in response. We couldn’t tell if it was from the drugs in his IV or something more serious—a kind of misfortune worse than death.

Ben’s mother was sitting next to his mobile bed. She shook her head. Her eyes were red and swollen. “William isn’t here,” she told us, and we understood what that meant, the tragedy of it coming to weight as the nurse ushered us out of the ward and into the stuffy air of the waiting area.

Later, we learned that William had slid his Honda CRV into a telephone pole at sixty-plus miles per hour, shearing his brainstem in the process. All injuries were internal, which meant his head never left the rest of his body, but two days later, Sam Donner said William came to him in his dreams with his head cradled under his arm like a jack-o-lantern. Debby Hohensinner said she saw him like that when she closed her eyes. So did Johnny Yu.

We skipped school for the rest of the week, drinking beer all day and listening to records in Debby Hohensinner’s living room while her parents were at work. Light shone through the curtains, casting the sofa’s huck upholstery and the shag carpet into a haze of dust particles and lethargy.

3.

From the very beginning, we had wanted to know the truth behind Vevay’s house.

The day that Johnny managed to climb the big oak tree in the backyard, we thought we had hit it big. He had tried to peer through one of the windows on the second floor, but edged too far out onto a branch. It collapsed under his weight and sent him crashing to the ground. When he came to, we asked him what he saw.

“Their living room,” he said. Then a shiver ran through him, and he shook his head in a kind of daze. “But it was real creepy.”

Around that same time, Debby sliced her leg open the length of her calf, crawling through a hole in the back of the Hollanders’ decrepit tool shed. The wound barely bled at all.

And later that week, Sam used a hatchet that Debby had stolen from the shed to cut down the tree that had almost killed Johnny, but the head of the hatchet slid loose and nearly chopped Sam’s leg off.

We carried Sam down to his mother’s house and rang the doorbell before leaving him on the front porch, a bloody mess.

“Where are you going?” Sam called as we dashed into the shadows between houses. He was holding back tears.

We knew we couldn’t answer, though. We only ran faster, because if Sam’s mom saw us, she would call our parents and tell them what we had been up to. It was important, above all else, that our parents not know we had been snooping around the Hollander house. Not that they had ever told us directly to avoid the Hollanders, but there was an understanding in the way that dinner conversation paused when the Hollanders were mentioned; even our parents, with their canned personalities, could see that there was something not quite right about the Hollanders. They never came to the neighborhood barbeques. They never rolled down their car windows to wave. They never seemed to smile. And so, when it came time to dole out punishments, their reasoning would be much more opaque. Our parents wanted us kids to mind our own business when it came to the house at the end of the street.

4.

William and Debby had seen Vevay through her window once. They had said she was sitting in her room, on the floor, alone, staring into the carpet.

“Conjuring spirits,” Debby said later from the rusted swing behind the Fairchilds’ pole barn.

We hung out behind the pole barn in the summer because it was just up from the creek, and we could see down the gully to the clearing behind Vevay’s house. Often we sat for hours, waiting.

Johnny sat in the swing beside Debby, lightly rocking and studying the scab of dirt underneath his feet. Sam stood by the edge of the woods, ripping twigs from a fallen branch and throwing them at Ben, who kept telling him to stop—but in a nasally whimper that seemed to only make Sam want to throw more. We were in middle school at that time, still wishing for complexity—using terror for tender.

William was leaning with his back against the A-frame of the swing set, staring down the gully with a glazed look in his eyes. “She was probably just lonely,” he said.

Sam laughed and threw a stick at William. “She was probably practicing her…” He paused to find the right word. “Incantations. You know, to kill you or turn you into a dog or something.”

“Why would she kill me? You’re the one who always picks on her at school.”

Ben, red in his boyish face, found a stick at the edge of the woods and hit Sam across the back of his legs.

Sam fell to the ground. “Ah! Why’d you do that for?”

“She’s probably just under the control of that house,” Ben said. “We should save her.”

“There’s no saving her,” Debby said. “She’s evil.”

“I don’t see what’s so evil about her,” William said.

“That’s exactly what she wants you to think.” Debby stood from the swing, walked to the edge of the woods, looked down to the clearing. A slash of light splayed across the dry and cracked dirt. All around it grew wild sumac and arrowhead. Patches of dandelion dotted the rolling hillside. There were secrets down there, terrible secrets. “Don’t let her fool you with that whole innocent routine. She is definitely evil.”

5.

We often wondered if William would have been alright had it not been for Jeff Marcus.

On the second day of high school, Jeff Marcus gave Vevay Hollander a crown of dandelions, changing the way we looked at her forever. We knew what those flowers meant—what we had been ignoring all through middle school—that the lanky figure with greasy hair and sloping shoulders was blossoming. She was becoming a woman, and Jeff Marcus saw it too. The only difference was that he had grown up on the other side of town, where opportunity was seen as more than a gift. It was seen as something to take, and he was trying to take Vevay from us.

The reality of the situation was that the transition between middle school and high school had been filled with surprises, the kind of social-political power moves that overturned popularity overnight. There were three middle schools that fed into Harrison High. The kids from Wesselman Middle, including us, were from the north. Country kids, really. The kids from Plaza Park Middle were from the East. Wealthy. Mostly, sons and daughters of upper management or engineers from the smelting plant. Then there were the kids from McGary Middle. City kids. Jeff Marcus was from McGary, and we envied him for what we thought were street smarts.

During these early days of reordering, we realized that we were going to need Vevay more than she would ever need us, because even at fourteen, it was clear that Vevay Hollander was going to be beautiful.

The day that Jeff Marcus surprised her with the crown of dandelions, Vevay had been reading a book in the dugout during lunch. When William heard about the gift, he spent the rest of the day searching the halls between classes until he found Jeff Marcus at his locker after the second bell to seventh period. They were the only two in the north hall at the time, technically late for class, and without a word, on turning the corner, as if he had surprised himself with his own rage, William sprinted the length of the hall and tackled Jeff Marcus to the ground and proceeded to pummel his face until the shop teacher came to break up the fight.

Later, William told us that he didn’t know what had come over him. Even as he told us, he seemed not to believe what he had done. “I couldn’t stop myself,” he said, looking at the tops of his hands, bruised over the knuckles. William was normally a calm kid, introspective, and the only explanation we came up with was the curse.

But at that time, we no longer wanted to believe it. Or more importantly, we didn’t want anyone outside our neighborhood to think we believed it. So, we ignored it. The first real sign that William was doomed, and we turned away, bargaining our fears the same way we had given up on Santa Claus and the Tooth Fairy.

The treetops in our neighborhood didn’t turn that year. They stayed green all fall, until the first frost ripped them clean from the puny branches near the canopy. All fall they looked like monks with bushy caps, calm and collected, brooding.

It was also the same year that William started inviting Vevay up to the pole barn to join us around a fire pit we had built to hide the fact that we’d discovered marijuana.

6.

We didn’t know the exact moment William had fallen in love with Vevay, but we did know the moment she had broken his heart, because Debby had been the one to do it when she accidentally told him that Vevay had gotten herself knocked up. We knew because Debby told us exactly what happened afterward: William had turned red in the face; he had run to his car; Ben had insisted he come with him.

At that time, Vevay had been missing for three days. We attributed her disappearance to the bun in her oven, but we didn’t know what to believe. Since pregnancy scares were becoming a common occurrence in high school, we thought Debby might have been lying, but two things convinced us. First, the way Debby had discovered Vevay was pregnant: Debby’s mom had told her, and she had heard it from Vevay’s mom. The two of them had bonded haphazardly once Vevay started to come out of her shell. And since Debby’s mom had nothing to gain from spreading rumors, we were led to assume that Vevay’s mom had told Debby’s on purpose, because it was widely known that Debby’s mom was pretty lousy at keeping secrets. We figured Vevay’s mom had wanted the secret to get out, in order to turn Vevay’s predicament into a kind of life lesson that would—in Vevay’s mom’s mind—knock some sense into Vevay. The whole predicament only seemed to add to what we already knew about the myth of the Hollanders.

The second thing to convince us that Vevay was actually pregnant was that William must have already known, because why else would he have brought a gun?

We didn’t find out about the gun until Sam tracked down William’s Honda CRV at Liberty Pull-A-Part, the scrap yard where most of our town’s totaled cars went to die a rusty death. In the police report, the officer on duty had listed the following contraband found in the vehicle: a bag of weed, one glass pipe, rolling papers, two roaches, one knife (kitchen, steak), one pair of scissors, one fifty-foot rope, one crowbar, one can opener (electric), one machete, and two miniature Louisville Sluggers. They had not found the Hi-Point 9mm that William had wrapped in bubble tape and stashed in the hold underneath the passenger seat floorboard. If they had thought to pull back the floor mat to reveal the rusted hole a little bigger than a fist, they might have found it.

No one could say why William had the gun. Like everything else packed into his clown-sized car, the gun could have found its way there unrelated to the trip across town that cost him his life. The gun had come from Johnny’s uncle, who had been hounding Johnny for the week prior, saying that if he was going to be a lousy thief, it would better suit him to steal a gun that wasn’t liable to misfire and blow off his hand. Johnny’s uncle was known to have an arsenal in his basement.

When Ben told us that he and William had been heading toward Jeff Marcus’s house, we thought that maybe the gun was meant for Jeff, that maybe William had stolen it from Johnny’s uncle with the plan to drive over to Jeff Marcus’s house a week later and shoot him—or at least give him a good scare—but Ben also told us that he was only guessing where they were going, because neither he nor William spoke a word during that short ride.

7.

The day of the funeral, Vevay walked into the viewing parlor wearing a white sundress with a layer of sheer fabric that billowed out from the bust and over the slight curve of her belly. It became clear to us then just how pregnant she had been and how remarkable it was that we hadn’t noticed. The ragged hem of her dress fell to just above her ankles, revealing the red Converse, faded and torn, that she had been wearing every day since the summer before. Her blonde hair was bleached white, frizzy and shorn to the nape. The sockets of her eyes looked sunken, much deeper than usual, and a dark scab marred her left elbow. The beauty we had come to see in her seemed thin and unremarkable as she stepped up to the casket and tucked a folded piece of paper into the breast pocket of William’s black suit jacket.

Johnny attempted to sneak a look at the piece of paper, but he said that William’s face had kept him from reaching into the pocket. The mortician had had a hard time covering the bruises around William’s jaw, and his neck wouldn’t sit quite right. To cover it, the collar of his shirt had been pulled high, which gave the impression that William had passed in a sudden moment of befuddlement.

We had all wondered what Vevay had written on the note. We watched from across the room as she leaned over William, awkwardly angling her belly to lean in close or to share a glimpse of the baby. Afterward, she stepped over to William’s mom, who had been shaking hands and accepting condolences beside a giant picture of William on a tri-fold next to the casket. Mrs. Smitt showed little sign of recognizing Vevay, let alone the baby brewing in her gut. Given Mrs. Smitt’s state, it was possible that she had blocked Vevay from her mind entirely, wishing to forget rather than forgive. Vevay hugged Mrs. Smitt, gripping her around the waist much longer than Mrs. Smitt seemed inclined to offer. Then she focused on the floor and started toward the side door of the funeral home. On her way out, she saw us and lifted a hand to wave but stopped herself and looked away.

Sam followed her, but he said he wasn’t able to catch up, that she must have disappeared, because when he reached the parking lot it was empty, save for a few drivers smoking cigarettes in the heat. After he returned to the parlor and told us she was gone, we stood there for a long time, silently watching all the uncles and aunts and cousins walk up to Mrs. Smitt and give their best attempt at making sense of the senseless. We never spoke about it, but it was entirely possible we had conjured that image of Vevay out of some need from our collective grief.

8.

When death had been an imagined tragedy, it was easy to believe we owned some part of it, as if life were made more exciting by the fables of our past, a tradition of grief. It wasn’t until the lines began to blur that we thought of ourselves differently. After William’s death, the function of grief shifted. It was no longer ours. Instead, it seemed to trail behind us. We began to see it in the way we moved through the woods. The shadows in the leaves. The squirrels at a distance. Behind the pole barn, the fire seemed to lick up the weathered planks skyward and outward, the direction we were all headed.

The night after the funeral, we sat around the fire pit until the sunlight began to shine through the trees. Vevay was with Jeff Marcus somewhere. We knew because Johnny’s brother had seen them leave the funeral home together. Jeff had been waiting for her in the parking lot in his Datsun sports coupe. We tried to imagine where they were: speeding down a highway through Tennessee, maybe Mississippi on their way to New Orleans. Or maybe they went to Chicago. Or even New York. We imagined all of these cities crumbling upon their arrival—intricate systems of class and wealth and public transportation folding in on themselves with the grief that accompanied Vevay wherever she went. There was a certain amount of comfort in visualizing the destruction of cities we had never visited. It was important that the curse survive us and that future civilizations crumble under the complexity of Vevay Hollander. At least it seemed important as we sat around the fire in close silence, divining from embers. This vigil, if we had shared a shred of altruism between us, could have been the truest indication we were actually grieving.

That was when two headlights pulled around the corner of the pole barn. The beams seemed faint in the morning light, glinting in the dew of the grass. Vevay was the first to climb out of the Datsun. She was still wearing the white sundress. The flush in her cheeks made it seem as though she had recently had a good cry. Jeff Marcus opened his door and hooked an arm over the top, doing his best to look intimidating, but by then we had come to see him as Vevay’s tool, just another boy caught in her wake.

Vevay took a few steps and stopped. “I just wanted to say,” she said and paused, cradling her belly, as slight as it was, with her hands. “It wasn’t my fault.” The words had a nasty cut to them, and she let her head drop to look at her feet, a habit she had when she felt uncomfortable. Her frizzy white hair fell forward and draped over her face. Then she glared up at us. “I’m just saying, because I never want to see any of you ever again.”

We were still sitting when she told us this, and Sam stood. We knew what he wanted to say, that everything was her fault, that we wished she had never moved to our neighborhood, and that if we never saw her again, it would be a blessing.

But then Sam pulled the High Point 9mm from the waistband of his jeans and shot Jeff Marcus through the driver’s side window.

The glass shattered. Jeff clutched his stomach. The pop of the pistol echoed over the trees, skittering a half-dozen crows. Then Jeff Marcus fell to the ground.

At the funeral, we hadn’t talked about how we felt. We had only mocked our parents as they glided around the viewing parlor like bees, pollinating with aphorisms. “Grief hits us all differently.” “Anger is a natural stage.” “It’s okay to be angry or even afraid.” “You can’t control grief, only accept it.” We had heard them all before—read them from the internet. The only problem was that our grief was different. Our grief was ours, or at least it had been until we lost hold of it. When it was us against Vevay, it made sense. We could follow our fears straight to the source, but as we grew older, the root of our fears blurred and our original hold seemed merely incidental, because in that moment right after Sam shot Jeff Marcus, the meaning of our grief pooled into a dark lump of clothing beside the driver’s side door of a Datsun sports coupe.

Sam stood silhouetted by the fire, his chest heaving with each breath. He had been out-growing his t-shirts from the start of high school, but his black Nervous Eaters tee seemed especially tight. No one thought to ask him why he had done it, and maybe it was the shock of needing to ask that had taken us by surprise more than anything.

Then Ben tackled Sam to the ground and knocked the gun out of his hand. They rolled into the fire. Ben’s jacket lit up along the hem, and Debby pulled off her sweater to smother the flames that flapped in the dewy grass.

Johnny only watched, jostling from side to side and looking from Ben to Vevay and to the dark lump of clothing beside the Datsun.

That was when Vevay ran for the woods.

Sam stumbled to his feet. He picked up the High Point 9mm and tucked the gun into his jeans. He looked back at us before starting after her. We should have called after him—told him to let her go—but the look in his eyes said not to. Besides, we didn’t know what to tell him. We thought he had murdered Jeff Marcus, shot him dead. We wouldn’t find out until later that Jeff Marcus had only broken a rib and that the High Point 9mm had been loaded with rounds of paraffin.

9.

Sam was the last to see Vevay Hollander. He told us that after he chased her through the woods, they stopped in a clearing somewhere past the far edge of the neighborhood. They were overlooking the creek from a steep embankment, and the silvered light reflecting off the water cast the brush and blowdown in sharp relief. While they had been running, Sam said that it looked as though every branch and knot of thistle had been pulling at Vevay, kicking up the hem of her dress and curling around the soiled brightness of its sheer fabric. He had been gaining on her, and she looked over her shoulder, looked again. Then she slowed to a stop. When Sam told the story, he made it seem like she would have run forever had she not seen him following her, and maybe she would have.

“What’s wrong with you people,” she said once she caught her breath.

Sam stepped close, but Vevay didn’t flinch. She seemed too tired. Not just breathing heavily from running and being five months pregnant, but from something else. There was something broken about her. The potential she had once had, the person we had all thought she would grow into, seemed further away than ever.

Winded himself, Sam reminded Vevay that he had a gun and she should be much more afraid than she seemed to be. Sam waved the High Point 9mm. “I could kill you,” he said.

“Not likely.” Vevay gathered the skirt of her dress and stood as if she were about to start off again. “Not with wax bullets,” she said and smiled faintly.

Sam turned and shot a tree. Bark splintered and fell. The recoil echoed the length of the creek. Then Sam saw it, where he had hit the tree, buried in the trunk, a glob of dark sapphire glinting.

We didn’t know how Vevay had known about the wax bullets. It was possible that Vevay had been in on something that we were never meant to be a part of. We talked about it for years afterward, how she had known before the rest of us, but in all that talk, we never gave voice to what we had all been thinking. Maybe there was no “we” at all, and there never would be.

“I could still shoot you in the eye.”

“Don’t you get it?” Vevay rushed Sam. She pushed him, and he fell on the ground. “Why can’t you just leave me alone? You people are crazy. You’re a curse. You ruin everything.” Her cheeks flushed. She looked as though she might start crying, but she stopped and looked up the ridge.

Debby and Ben had started walking after them. Vevay must have heard their clumsy steps through the brush. Vevay pushed Sam into the ground one last time, then started up the steep hillside toward the edge of our neighborhood.

“Wait,” Sam called after her.

Vevay paused and looked back over her shoulder.

“What did you write in that letter?”

Vevay took two steps toward Sam and leaned over him. “I told him I was sorry. I tried to save him from you people, but I couldn’t.” Then she turned and started back up the hill.

10.

Johnny’s brother said that Vevay had been shipped off to a school for pregnant teenagers, but at school, most rumors circled around an insane asylum upstate. There was even a kid who said Vevay had killed herself and her baby in a ritual sacrifice. We tried to stay out of the rumors. We didn’t want people to know what had really happened that night.

A few days afterward, Sam saw Jeff Marcus standing at his locker talking animatedly to three other boys. The three boys were chuckling, and Jeff raised his shirt to show off the brace he wore for his broken rib. When Sam walked by, he caught Jeff’s eye, and Jeff stiffened. He lowered his shirt and, forcing a short chuckle, slapped his locker shut. Then he started off to class in a hurry, leaving the three boys to look stupidly at one another.

We heard later that Jeff had made up a story about his broken rib. He had been telling people that he got it at the batting cages in Garvin Park. Everyone knew that those pitching machines were old and unreliable, and Jeff had made himself out to be a kind of tough guy for taking the pitch without falling to the ground. We never thought to challenge it, even though those pitching machines would probably kill someone if they were hit directly in the chest.

That same year, Vevay’s parents moved out of the house at the end of Negley Avenue, and for years, the house sat empty. Birds roosted in the window sills. Hornets overran the back porch with a colony of nests.

The summer after we graduated high school, before we all moved away to separate colleges, we decided to break into the old Hollander house. Sam broke the window out of Vevay’s old bedroom. We knew she had moved into the basement after her brothers moved out of the house, so the room we broke into was a guest room for the last two years that the Hollanders had lived there. Before then, we had never seen a house completely empty, and even years later, when each of us began to have our own lives and raise our own children in houses we had to fill on our own, no house would ever seem as starkly vacant as the Hollanders’ house did on the day we walked through it and took inventory of the smudges on the base board or the lone chip in the paint near the corner of a room.

We walked downstairs to the last bedroom Vevay had lived in before she disappeared. William had told us she had moved down to the basement to get away from her parents. He had also told us that she moved down there so she could sneak him in through the hopper window after her parents had gone to sleep. We wondered about the nights they had spent down there together. William had never talked about it much, only saying that they were fucking. But once we got older, while lying in bed with our husbands and wives, thinking back to those times, we often pictured Vevay and William lying in that basement, sharing a cigarette or weed and talking about the future they were going to have together.

We stood in her room and scanned the walls. Johnny found some writing in the back corner of the closet. It said, “Derek and Blake were here.” They were Vevay’s older brothers. Then below that it said, “So was Vevay.” And below that it said, “And William too.”

John Thurgood is the nonfiction editor of the Southern Indiana Review. His stories have appeared in Another Chicago Magazine, The Evansville Review, Monkeybicycle and others. He writes book reviews for Electric Literature and a monthly fiction column for News4U. His MFA in fiction is from the University of California, Riverside.