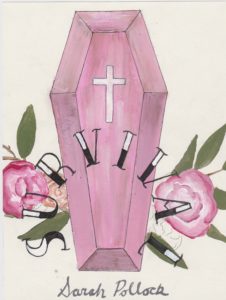

Sarah Pollock

That morning decades ago, when she was twelve and had seen Emma Weaver’s death notice in the newspaper, Janet lifted the sash on her bedroom window and gazed at her younger brother Andy in the dry, ploughed field below. Late summer had yellowed the grass that sprang from hardened dirt clods, and he sat cross-legged beside a creek bed that wouldn’t carry water until winter. Janet watched as he snapped a piece of bamboo from a clump that grew wild there and began to carve holes to make a flute. He held it to his mouth to test the sound. Even at ten, Andy could sit quietly for a long time, and he knew everything about particular things: which weeds were milkweed and mustard, which were anise and sweet grass. He could tell the difference between live oaks, blue oaks, and black oaks, and he had taught Janet to make fragile flowers by running her fingers up the seed pods of thistle grass. The pods made a star cluster in her fingertips that she blew away with a wish as if it were a dandelion blossom. While she watched, Janet thought about going down to Andy and telling him Emma was dead. She thought he ought to be told, although she also feared her dad was right when he said that Andy would suffer.

She leaned on her elbows and tipped her face into the heat, smelling the dry air of summer, and she saw her dad as he came around the side yard and walked toward Andy, his black sneakers kicking up dust from the field as he rolled up his sleeves. He must have changed his mind. Chuck stood next to his son, who held his flute, waiting, and then their dad leaned down and put the flute to his lips. Janet watched him laugh and shrug his shoulders, probably because he couldn’t get the flute to play a note. Nothing about the exchange seemed serious, and Janet wondered if her dad would tell Andy after all. But then he crouched down and sat beside his son in the dirt. Janet could see that they spoke, and she saw their dad put his arm around her brother in a sideways hug. Then Andy just sat there with his flute while Chuck sucked on a piece of grass, and after a long time Chuck got up and returned to the house. Andy didn’t leave; he just lay back and put his hands behind his head and stared straight up at the cloudless sky while a red-tailed hawk circled overhead, looking for prey.

Janet wished she’d never read the paper that morning. She’d been at the kitchen table, her elbows sticky from jam, when she’d been startled to see a familiar face she couldn’t quite place. She read the story and found it was about the death of a ten-year-old girl, a classmate of Andy’s, and in her excitement hadn’t considered what that would mean to Andy; instead she had relished the self-importance of having adult news to deliver, news that would make her parents pay attention for once. She’d felt a surge of excitement because something important had happened, something that connected her to something larger, a more grown-up world. She hadn’t felt sad because she hardly knew the girl, but she recognized the class picture Andy had shown her in June when he had told her that a friend of his was dying.

“What are you talking about, Andy?” she’d said then, thinking he had made it up.

“Leukemia,” he said. “She found out in the fall and now her hair is gone. She always wears hats to school.” Andy was only ten, and Janet, who felt much older, hadn’t thought he understood about things like terminal disease. Now it appeared he had told the truth. She knew Emma Weaver only slightly, pictured her as a tiny girl whose long brown braids flapped behind her when she ran, and she was good at running, could outrun anyone in her grade. Emma was the younger sister of a boy in Janet’s grade, and Janet had seen Andy walking home with her and been surprised that they were friends, because he mostly hung out with boys.

While Janet was reading the paper, her parents had argued down the hall. It was almost noon and Chuck, who was a lawyer, hadn’t yet come out of the bedroom. Earlier, Janet had taken him his coffee when her mom asked her to and had found him upright in bed in rumpled cotton pajamas. His hair was crushed against his temple and his beard was a mess of stubble. Janet had stepped back from the sour whiskey smell emanating from a glass on his nightstand and left the room.

After she read the obituary, she considered what to do. She was aware of her parents’ fight, but the news seemed too big to contain, and she wanted to deliver it. She knew her parents would listen, and she anticipated the feeling of being heard. She folded the paper with care and walked across the dining room and down the hallway to the master bedroom. Through the door, she could hear that her parents fought like sparring dogs, growling and circling but not yet fully engaged. Carol wasn’t crying, so Janet knew the fight hadn’t gone too far. She knocked once, then louder, and pushed open the door. Her dad still sat in bed and her mom slouched in the rocker. Both of them gazed at her, startled, their faces united by feral expressions they tried to mask.

“Why didn’t you knock?” said Chuck. “We’re talking.” He spoke curtly, with irritation, his voice laced with the suppressed anger that accompanied a quarrel.

“I did. You just didn’t hear me,” Janet said. She held the paper in front of her. “Look, Emma Weaver is dead.”

“Who’s Emma Weaver?” Chuck asked. He reached for the paper.

Carol leaned over and gazed at the picture. “Chuck,” she said, “that’s the girl in Andy’s class. Remember the one who was so sick in the spring.”

“Oh Christ,” he said. “This is all we need.” His unexpected irritation surprised Janet, who had been focused on the importance of having big news and hadn’t considered that the girl’s death might anger him. And why should it? Maybe it wasn’t about the death at all.

“What did you have to go dig this up, for?” he said to Janet. “Why are you reading the obituaries?”

He turned to Carol. “I think we should just forget we saw this. Remember how Andy was after his turtle died last year? I don’t think I can stand months of him moping around the house. If he couldn’t handle that, how’s he going to deal with this girl dying?” Chuck had little patience for his son’s soft feelings, which made him feel embarrassed and helpless.

They all grew quiet, and Janet tried to think what to say. She remembered what happened to Andy’s turtle. He had let the turtle go for a walk on the back patio, and it cut its leg on a piece of glass and died the next day. Andy wrapped him in tissue paper and put him in a shoebox and buried him under the pepper tree, crying the entire time. All day, he looked like someone had punched him in the stomach. At church on Sunday, Janet heard him ask God to bless the turtle; Chuck heard, too, and after Mass he barked that prayers were too important for dead animals, that praying for a turtle was completely inappropriate.

Janet had felt sorry for Andy for losing his turtle, even though she also thought he overdid his grief. After all, he could perfectly well have gone down to the shop on Cedar Street and gotten another one. She’d never had a pet and didn’t especially want one, except once in a while when she wanted a dog that she could run with. But Andy got really depressed and went around acting like no one else had never lost anything they’d loved. He was too sensitive, and he acted like he was the only one who had feelings. She was just tougher, that’s all.

After the turtle, Andy refused another pet. Instead he watched the gophers as they emerged from their dirt mounds or observed the waxwings as they built nests in the pyracanthus, and that seemed to be enough. Once he even watched a rattlesnake slither across the back patio, its rattle announcing its lethal presence while Andy kept perfectly still, attentive and unafraid.

Carol started to talk. “Emma is dead, and if someone doesn’t tell him, Andy’s going to find out anyway when school starts.”

“Let it wait, then,” said Chuck. “Summer will be over and it’ll be in the past.”

“I don’t think that’s right.” Carol’s voice still had some of the edge from the fight. “You always think you can avoid things by not facing them, but it doesn’t work. Things just get worse.”

“Hell, Carol, we’ll do whatever you want. I’m just trying to save the boy some pain.”

The conversation had gone in a different direction than Janet expected, but she should have known. Why should Emma Weaver’s death be any different from anything else? Her parents fought over money and the house and their friends and her dad’s long hours, but still she hoped that if something was important enough they could agree, they could act in concert, they could respond with the kind of united front that parents are supposed to have.

After their dad spoke to him in the field, Andy hadn’t come into the house until dinner. He sawed at a pork chop and poked at his string beans and didn’t speak. Janet watched the shadows on the table created by the summer light that filtered through the branches of the pepper tree. She liked the green of the beans on the white plates. Her mom and dad’s fight appeared to be over, and they seemed to have fixed something between them, at least for now. They talked about what they would do in Flagstaff in August, when the family would visit Carol’s sister and see the Grand Canyon for the first time.

Janet listened with annoyance, frustrated that neither parent spoke about what was important or acknowledged Andy’s sadness or her own role in bearing the news.

Two years ago, when her grandmother died unexpectedly, her parents had been much the same. There had been a phone call, her mother in tears, closed doors, a brief announcement to the kids. Janet, who knew her grandmother only from summer visits to Denver, climbed into the playhouse and was wracked with sobs because her grandmother wasn’t Catholic and was therefore destined to an afterlife in purgatory no matter how many prayers Janet offered up. Her father found her there and was flummoxed by her limitless grief for a grandmother with whom she had spent so little time. When she finally explained, he was unusually kind.

“That’s not true,” he told her, “no matter what the nuns have said.” Her grandmother, he said, was a good person, and that is all that God required. It didn’t matter that she wasn’t baptized. He put his arm around her shoulder and held her as her sobs dwindled and finally stopped. Her mother had flown to Denver alone and returned days later with a flyer from the service but little to say.

Now Janet interrupted them. “I want to go to Emma’s funeral,” she said abruptly.

Her parents looked at each other, forming an unspoken alliance. “I don’t think so, Janet,” Chuck said. “No.”

“But I’ve never been to a funeral.” She couldn’t have said why it mattered so much, but suddenly she knew she had to be there, had to witness the girl she’d once seen fly across the playground be buried. There was something so final about it, so frightening, and yet also darkly seductive. The funeral was a passage into something that seemed at once unimaginable and absolutely certain. She turned in silent appeal to her mother, who sometimes took her side.

“It’s a private thing,” her mother said, denying her. “You didn’t even know Emma.”

“But I want to go.” She crossed her arms and stared straight ahead. She knew her dad could explode but she didn’t stop. “I know her brother, and people I know will be there. It affects all of us.”

Andy scraped his fork across his plate. “Let her go,” he muttered.

After a long silence Chuck relented. He had a softness in him that could emerge unpredictably, as unexpected as the rage. “Fine,” he said. “I don’t think it’s what you really want, but I’ll take you both.”

Yellow chrysanthemums covered the white casket, which was pushed down the center aisle of St. Mary’s Church on a trolley by several boys and men whom Janet didn’t recognize, except for Emma’s brother. Lilies in big vases lined the altar. The yellow and white colors surprised her; she had thought a funeral would be full of black. Some people wore dark colors, but most did not. She grew hot in her navy plaid dress, and she smelled Andy’s sweat through his blazer.

The priest droned on and Janet tuned out. She tried to think of Emma in the white coffin, dead. She tried to think of what it meant to be dead and found that she couldn’t. The priest talked about heaven, and she couldn’t think about that either. Despite all her Sundays in Mass, ever since her grandmother’s death she hadn’t believed in a heaven or a hell. It was hard enough to believe in an earth that extended beyond the horizon. They say we live on a globe, she thought, and they take pictures from the moon to prove it, but sometimes the thought seemed as strange as the idea that humans were made of atoms and molecules. Skin and blood she understood, because they were real. She had seen the way a puncture wound would let the blood ooze out until it coagulated and dried into a brown crust and fell off, exposing pink new skin.

Emma Weaver never had a puncture wound. There had been no blood, except the failure of the blood inside her to do its job. There had been no visible signs, no evidence she was sick, and Janet didn’t understand how that could happen. She shuddered at the lack of warning. The idea of the emptiness that Emma had now entered filled her with fear. She wondered what Andy was thinking about. She could see only that he leaned his forehead against the back of the pew in front of him, and his eyes were dry.

He didn’t cry at the burial, either. They had followed the hearse in a long line of cars interrupted by stoplights and traffic. Then they stood on irrigated grass in the dry heat of summer and tried to listen to the priest, whose voice was too low to reach the back of the crowd. Girls sniffled and Emma’s brother sobbed next to the parents. The family placed yellow roses on the coffin, and everyone straggled off to gather at their house, but Chuck insisted they had been through enough. So they went home, and when they arrived Andy and Chuck remained alone in the old Volvo for a few minutes. She heard her dad ask Andy if he was all right, and Andy said yes, he was okay, he just didn’t feel like talking. Then Chuck got out and Andy stayed in the car alone, cranking the window up and down as he stared at the dusty windshield.

“How is he taking it?” Carol asked when they came into the house. “Not sure,” said Chuck. “He hasn’t cried at all.”

Carol looked worried. “Do you want a beer?” she asked. Chuck nodded and slid down on the couch.

“I hope we were right, Carol, about taking them to this funeral. I hate all that talk about death and salvation and purgatory and hell.”

“They’ve got to think about it some time,” she said. “We all do.” And she went into the kitchen to get the beers.

In the middle of the hot afternoon, while she sat at her desk laboring over summer math homework, Janet heard a muffled animal noise coming from Andy’s room. She walked across the hall, knocked on his door, and pushed it open, and she saw that he lay flung across his bed sobbing. She had never heard anyone cry like that. She put her hand on his shoulder but he yanked away and Janet wasn’t sure what to do, so she just sat quietly on the end of the bed. Finally, he took a deep breath and began to talk. As he spoke, he hiccupped and cried at the same time. “I didn’t think she would really die,” he said. “She didn’t seem that sick.”

Janet went to the bathroom for toilet paper, which she handed to him, and he finally sat up, shuddered, and blew his nose. His crying slowed as they sat side by side. “She told me things, said I was the only one who paid attention. It was kind of strange how we got to be good friends for a while.” He stopped, then started again. “She said she wanted to be kissed before she died, and I knew she hoped I would do it, but I didn’t want to. So she quit talking to me.”

Andy looked up. “Now it’s too late. Why couldn’t I just do it?” His small face, which still held traces of the round baby he had been, was ravaged with regret. It had been impossible for him to imagine that Emma would one day cease to exist. It’s unimaginable that a girl whose hand you can brush, whose pulse you can feel beating through her wrist, could be erased, disappeared, gone from this world. He had touched her skin, felt its warmth, and now she had vanished, mysteriously and forever.

“You can’t think that way, Andy,” Janet said. “You’re only ten. It’s not your fault.”

“Maybe,” he said, but she could tell he was only saying that to please her. She knew he was right, that even though he was only ten he already understood that it is possible to make mistakes, and that it can be too late to fix them. She felt a sudden terror as she realized that both of them would die and everything they had ever said or done would be fixed in time, unchangeable forever. And her parents, too, would die, most likely before them. That was unimaginable, and to even try to think of it felt like falling off a cliff into a darkness so vast there seemed to be no bottom. Even though she hated her parents’ battles, and hated all the anger in the house, the idea of a world in which they no longer existed made her breath stop.

Later, Janet saw Andy under the pepper tree, playing his bamboo flute. The sound was raspy and ugly. He played the same three notes, over and over. He played and stopped, played and stopped, poking at the dirt beneath the tree. Abruptly, he cracked the flute across his knee, hard. He grimaced as the wood splintered, and he buried his face with his hands. Then he stood up and kicked at the dirt with the heel of his foot, making a shallow grave in which he placed the flute. He covered it and walked away. Janet’s stomach hurt.

Janet and Andy never talked about Emma Weaver after that. For years, they didn’t talk much about anything else, either. When they were teenagers, his silences and depressions bothered her, and she knew that he thought she was cold. She rarely showed her feelings, and she learned to make jokes that distracted from life’s undertow. Then life went the way life goes, and after a while nothing about their childhood mattered quite so much. Their parents had gotten divorced, finally, and Chuck found a new wife who was younger and thought he was sexy when he drank. He blossomed for a while. Carol went back to school and became a public health nurse.

Andy became a carpenter and lived in a cabin he built in the Sierra foothills. Janet, who was busy with her law practice, would have said they were on good terms, although she rarely visited. Even in adulthood, she often found his moods hard to take, although now that she was older she also liked his kindness and recognized how deeply the two sides were related.

One icy January night she had dinner with him after cross-country skiing all day. She had been out on the trails while he stayed home to work on a project, but now they passed the evening together. In their early thirties, neither had married, and both still lived alone. Their conversation was laconic, composed of sentence fragments about inconsequential things and laced with the silences they were both accustomed to.

“I saw a fox out there, in his winter white,” she told Andy. She had tried to stay as still as she knew her brother would have done, but the fox had felt her eyes upon him and vanished as silently as he’d appeared. Only his tracks in the snow offered proof that he’d really been there. Andy nodded, and when they finished their meal, he poured them each a glass of port. She watched him slice up an apple, and she thought he would offer her a piece, but instead he opened the front door, walked down the steps, and deliberately spread the slices out in the snow.

When he returned to the table Janet lifted her eyebrows. “I know you’ll think I’m nuts,” he said, “but there’s a family of mice under the porch that I’m trying to help survive until spring.” It’s pretty cold, he added, and he liked to do a bit to help wherever he could.

She flashed a smile of recognition and stopped herself from making a crack. The mice would probably be fine, she thought, unless her white fox stopped by. But she didn’t say that. Despite his beard and broad shoulders, Andy was still the same little brother who was shattered by his failure to kiss a dying girl at ten. Who had been too young to kiss anyone at all, but who had thought he should have done so anyway, and was filled with remorse at his failure to give that modest gift. She was sorry she hadn’t been able to help him better then, sorry that in those days things had been so hard for both of them. Now, instead of turning away, she lifted her glass. “To wild mice,” she said. “To survival.”

Sarah Pollock has written numerous nonfiction articles, essays, and book chapters for publications ranging from Mother Jones and California Magazine to various anthologies. This is her first published fiction.