Amechi Ngwe

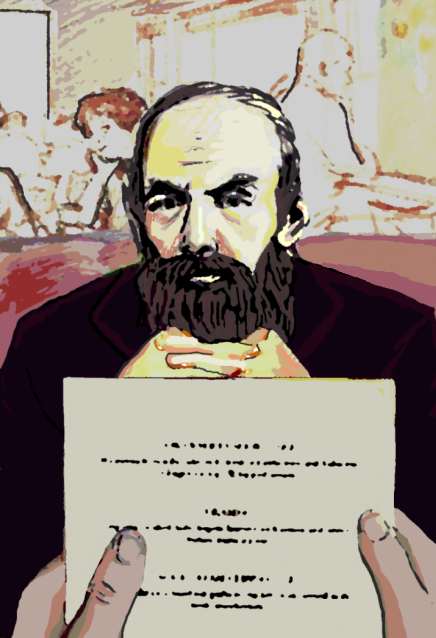

I’m having lunch with Fyodor Dostoyevsky because I entered a contest to win a lunch date with swimsuit model Innuendo Fernandez and ended up with the consolation prize: a lunch date with Fyodor Dostoyevsky. We shake hands when we meet near the entrance and then there is a long, awkward silence while we wait to be seated, which I guess is okay, because Lucia’s Mexican Kitchen is pretty busy at lunchtime and we would have to shout to be heard. I’m scared to talk to him anyway; my Russian is terrible. I only know five words, four of them swears, learned from a tall, blonde Muscovite named Josefina whom I dated for a few weeks last year. If I needed to say hello and then insult his mother I have it covered, but hopefully things won’t go in that direction.

to win a lunch date with swimsuit model Innuendo Fernandez and ended up with the consolation prize: a lunch date with Fyodor Dostoyevsky. We shake hands when we meet near the entrance and then there is a long, awkward silence while we wait to be seated, which I guess is okay, because Lucia’s Mexican Kitchen is pretty busy at lunchtime and we would have to shout to be heard. I’m scared to talk to him anyway; my Russian is terrible. I only know five words, four of them swears, learned from a tall, blonde Muscovite named Josefina whom I dated for a few weeks last year. If I needed to say hello and then insult his mother I have it covered, but hopefully things won’t go in that direction.

I quickly realize that he speaks English well and we have a brief, fractured conversation in which we both comment on how busy the restaurant is this afternoon and wonder aloud if we should try somewhere else instead. But neither of us can think of another good place we’d both like to eat and then the beeper we’ve been given to tell us when our table is ready sounds, so we decide to stay. “I’ve never had Mexican food before,” Dostoyevsky says and now I feel like the pressure is on me, since I chose this place, to make sure he enjoys the experience.

We are shown to our table and our waiter, Antonio, asks us what we would like to drink. He refuses Dostoyevsky’s request to bring two bottles of vodka to the table so I order us two bottomless margaritas, on the rocks, with salt. When our beverages arrive Dostoyevsky is intrigued by the chartreuse color of his drink, but isn’t wild about the taste judging from the way he scrunches up his face when the first sip passes between his lips. Antonio smiles and gives us a few minutes to look over the menus. While Dostoyevsky searches his menu for something he finds appetizing, I hide behind mine and try to think of a conversation starter.

I wonder if I should talk with him about writing but remember that I’ve never read any of his stories because I’m not well-read, and he won’t have read any of my stories because according to the editors of numerous Literary Journals they’re not well-written. Then I wonder if I should try to discuss politics—normally a taboo subject at mealtimes for me—but I can’t say I know anything of 19th century Russia’s Political Climate, or even today’s for that matter. I try to think of something interesting I’ve seen on TV that we might be able to talk about, but the shows I can recall watching recently are The Voice and America’s Best Dance Crew, and it’s unlikely that he’s seen either one of those and I’m too afraid to ask if he has.

Antonio returns, and Dostoyevsky complains that he can’t find jellied pork or pickled eggs anywhere on the menu. “We don’t have those,” Antonio says in accented English and then he gestures to the menu, “but I recommend the pulled pork quesadillas and Huevos Rancheros.” Before the old master can reply, I order the lunch enchiladas for him and lunch fajitas for myself. I go with items from the lunch menu because it’s a few days before payday and, as always, I’m struggling to make it through the final days. This is also why I ordered us the bottomless margaritas. It’s the economical option when you know you’ll be having more than two drinks and they are of course made with the cheap stuff (probably the Pendejo brand Tequila my friends and I used to drink when we were freshmen in college), but I don’t think Dostoyevsky notices; at least he won’t until he gets home tonight and discovers that he has the runs.

Antonio leaves to put our order in and after another long silence I make a comment about the weather being warm for this time of year. Dostoyevsky’s response touches on the nature of love, the devil, and doctors, and is too deep for me to comprehend. Then I notice that Dostoyevsky’s fishbowl-shaped glass is empty. He is chewing on the straw and staring at the other people in the room so I order us a pair of fresh margaritas the next time Antonio is passing by.

“Margarita,” Dostoyevsky’s voice booms as Antonio plops our new drinks down in front of us. “Maar-gaaar-reee-taaa,” he repeats, drawing out the word so it sounds like thunder. I guess he likes the word and my assumption is confirmed when he asks me where the name comes from.

“The drink is named after a woman,” I tell him. I’m not sure if that’s true, but it sounds plausible, and I say it with enough confidence and authority that he thinks I’m an expert and doesn’t question me.

“Yes, just like a woman,” he says, scratching at his chocolate-brown beard. “At first sweet, but after a while your money’s gone and you realize she gives you a headache.” I wonder if the alcohol is loosening him up and he is attempting a joke, but with his thick beard obscuring his mouth it makes it difficult to tell if he is smiling. Then he makes a comment about god that passes as far over my head as a rain cloud, but thankfully brings us to the topic of current and former lovers. He tells me that he is, at the moment, free of romantic attachments and then speaks about his former wives with fondness. I sense a tightness in his voice whenever he says their names and when he finishes he clenches his hands on the tablecloth as if trying to hold the hands of those long-gone women one final time. Then he tells me that losing them was good for him because he was able to pour all of that emotion and energy into his writing and look how that had turned out.

And then I think to myself that he’s clearly not over them yet.

He asks if I am married and I tell him that I am not. Then I mention the funny fact that the first names of the last seven women I’ve been involved with all began with the letter ‘J.’ I tell him I found it strange, and that he could use it in a story if he liked and he tells me that it sounds like something Tolstoy would do.

A few moments later I realize that he said Tolstoy’s name like it is a curse word.

“Did your girlfriends’ names also all have vowels?” He asks, twirling the straw in his glass to make a mini-whirlpool. I would be sure he is poking fun at me if it were not for the intense look in his eyes. Then he says, “Come now; let us talk of serious things.”

“Okay,” I say, knowing that this is the chance to asks one of the greatest minds in history a question of great importance. Maybe I can learn something that will help my writing. “What do you think the meaning of all this is?” I ask, gesturing to everything around us.

“That’s easy,” he says. He leans across the table say in a low voice. “This is a place where people come to eat when they don’t want to cook.”

“No,” I say. “I mean life. What is the meaning of life?”

“That’s an easy one too,” he says.

Fyodor Dostoyevsky is in the middle of explaining the meaning of life to me using items on the table as props, and I’m wishing I had a pen to take notes and trying to remember if the saltshaker or the bowl of salsa is supposed to represent Mankind, when the sound of a nearby sizzling fajita skillet interrupts him. Our food has arrived. Antonio carefully places plates of hot food between us until our table resembles a photo from the menu, then warns me to be careful with my hot skillet, gives us a slight bow, and wishes us a good meal as he departs. Dostoyevsky studies his plate, which is holding rolled tortillas filled with chicken and topped with sticky cheese and then he picks up his fork and cuts into the gooey food.

I twirl my fork between my thumb and forefinger and nervously watch him take his first bite. “How is it?” I ask as he chews.

He rests his elbows on the table and steeples his fingers as he contemplates my question, and then a moment later his dark eyes narrow. “Bad,” he says. “Very bad.”

Blood rushes to my cheeks as I felt the embarrassment of having disappointed one of the great writers of history by ordering sub-par enchiladas for him. “I’m sorry,” I say. “My ex, Josefina, told me they were good.”

“Nothing is always true.”

“That’s true…well, sometimes, but I thought I could trust her judgment.”

“It’s a human need to be sure of at least one thing,” is his mind-boggling reply.

“Can I get you something else then?” I ask as I raise my hand to signal Antonio.

“No, no.” Dostoyevsky shakes his head and the end of his beard sways like the branches of a tree in a rainstorm. “For life is pain as well as joy,” he adds as he looks down and cuts another piece of cheesy goo and stuffs it into his mouth. “We must accept suffering because out of suffering can come inspiration.” He grimaces as he chews, and his eyes begin to water, and while I make a mental note to never order the enchiladas, he quickly chases the mouthful of food with a gulp of cheap tequila, artificial limejuice and sour mix then stares at the half-full glass like it is a sworn enemy. “And this drink,” he says, “I drink so I may suffer twice as much.”

I go to work on my fajitas, scooping rice, meat and vegetables onto a warm flour tortilla, lean over my plate so the juices don’t splash onto my shirt, and then take a bite. Then Dostoyevsky’s shadow falls on my plate and I look up and see him leaning across the table. There is a yellow blot of queso in his beard and his eyes are locked on my plate, the same way my eyes would be locked on Innuendo Fernandez if she were seated across the table from me in a lemon and lime colored body paint bikini and was giving me her bedroom eyes. Dostoyevsky’s nostrils flare as he sniffs the air. “That smells angelic,” he says.

I swallow the bite of food I am working on and say, “Thanks.”

“The perfect counterpoint to my deplorable pigswill. Why didn’t you order one of those for me?” He jabs his knife at my still-sizzling skillet then rests his hand on my side of the table. “I like the hissing plate.”

I say, “I really thought you’d like that,” and gesture to his enchiladas with my knife.

To my surprise, my verbal and physical ripostes repel his attack on my lunch and he retreats to his side of the table. He picks at his enchiladas with his fork and says, “It is adequate.” Then he cuts a tortilla open and extracts a piece of chicken with the expert precision of a surgeon. “We shall try some dessert next. How is the fruitcake here?”

“Actually,” I say, “I’ve already ordered us dessert.”

“Fruitcake?”

“Something else.”

He slumps back in his seat and says, “I thought I be able to choose my own dessert on my birthday.”

“Oh, it’s your birthday today?” I say, feigning surprise. “I didn’t know that.” This is a lie, because I caught a glimpse of Dostoyevsky’s ID when Antonio asked to see it before he brought us our adult beverages, then I discreetly made the necessary arrangements.

But Dostoyevsky lets me know his birthday isn’t that important to him by saying something like, “It’s not important. I find birthdays to be a useless tradition full of noise and nonsense. Strangers, rational people, becoming wildly excited about my birthday, feigning joy that a day later they’ll forget. That infuriates me.”

“Really?” I ask.

“I prefer to honor the day I was almost executed. I cannot recall any day as happy as that one. But birthdays? Give me peace, quiet, and a slice of fruit cake, or give me nothing!” he says and emphatically bangs a fist down on the table. “What was I talking about before? Ah yes, the meaning of life!” He grabs the saltshaker. “It’s quite simple actually…”

I miss what he is about to say because just then the Tres Leches cake and mariachi band I requested to celebrate the birth of the Prophet of Paradoxes comes streaming out of the kitchen. Antonio is at the head of the line; the small cake held up in front of him like a battle standard. The band members, each of them wearing a large black hat and bearing arms in the form of a brass-colored trumpet, black violin or brown guitar, march along behind him and my heart starts to beat a tattoo as if it wants to join the band. I try to halt the advancement of the procession with a disguised wave of my hand, pretending I’m batting at a fly, but they keep coming. As Dostoyevsky continues his explanation I mouth, ‘No’ over his shoulder and then I shake my head at them when Dostoyevsky lowers his eyes to find his margarita, but to my dismay they march on.

They weave around crowded tables and approach Dostoyevsky from behind to keep the element of surprise. Then they’re so close that if Fyodor reached back he could touch Antonio’s arm. Antonio steps to Dostoyevsky’s right and the mariachis fan out around him turning their column into a line formation. Horns are raised to pursed lips and eager fingers and primed bows are positioned over taut strings as they point their instruments at Dostoyevsky’s back and prepare to unleash a volley of sound. My mouth opens and Spanish words fly out. Because of these words only one mariachi strikes a chord on his guitar and it sounds dissonant and flat. Instead of singing the opening bars of their birthday song, Antonio’s mouth hangs agape and the cake tumbles from his hands to the floor.

Unfortunately, having learned the Spanish language from foul-mouthed friends, my Spanish is only slightly better than my Russian, and just as vulgar, so in my flustered condition instead of asking them not to start the song and to return the cake to the kitchen, I have launched a verbal cannonade at them which is the Spanish equivalent of “Your mothers look like manatees and pleasure goats for a living!”

While having the effect of preventing the cake from being delivered, it also causes a lot of shouting (at me), some pushing (of me), and despite my apologies and claims that my words may have been taken out of context, the end result is that Fyodor Dostoyevsky and I are quickly hustled out of the building.

I’m tossed onto the pavement and look up to see the old master of words dusting off and straightening his dark coat. I stand up and my lower lip trembles as I prepare to offer him a thousand apologies for my mealtime mistakes.

“This was disastrous,” Fyodor Dostoyevsky says. Before I can agree with him he adds, “And also quite pleasant,” his voice softer this time. “I feel inspired to write a new story.” Then he claps me on the shoulder and says, “We should do this again.” And with that he ambles off.

Amechi Ngwe was born in London, England, but currently resides in Houston, Texas. His work has also been published in Structo Magazine and Jersey Devil Press. He can be reached at amechingwe@gmail.com.